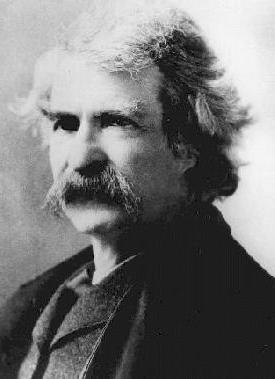

Mark Twain

Excerpts from "Roughing It", Territorial Enterprise, and other tales

During the great rush for the wealth of the Comstock, Virginia City's daily newspaper, the Territorial Enterprise, had need of another writer to keep up with the demand for news. A hungry, scraggly, dusty, "coyote-hole" miner showed up at the door to answer the need. Sam Clemens found that he was much better suited to the job of writing about his observations than he was to doing manual labor like digging holes for gold and silver. We know him today as Mark Twain, the American humorist. Twain honed his writing skills during this period and had many opportunities to express his unique style of humor. His influence continues today, over 100 years after his death in 1910, largely due to his experience at the Enterprise. Twain took illogical human traits and aired them for all the world to examine. He wrote as a person stuck in a time which was not his own. People either loved him or hated him for his social commentary when they saw their own traits condemned as false thinking in his popular stories. His admonishment of racism in "Huckleberry Finn," foreshadowed the future of America's civil rights movement. Today, people still seek to ban this book. Yet, the legend of Mark Twain lives on wherever English is spoken.

In the Footsteps of Mark Twain

Around the World ~ A Lifetime Pursuit of Experiences

Mark Twain was a bigger-than-life man even when he was alive. When you read his daughter's story about him, you realize that he was the same person that we all know ~ all the time ~ not someone else with his family and someone else with us. The magical thing about him was that he allowed people inside his thoughts, and his thoughts were slightly aschew of everyone else ~ at that time.

Twain was most certainly living ahead of his time. He had that backward perspective that is usually only gained after the history is written. His gift ~ his talent ~ was the ability to express himself in writing. Story-telling on paper and using words which conveyed his mindset ~ his humor. It seems to me that he must have had his tongue lodged tightly against his cheek as he wrote down some of his pieces.

I can remember as a youth reading some his writing and thinking, "why you silly man, of course that's the way it is." It is only now as an adult that I recognize that in HIS time, the things he was writing were novel and that few had written of things that way. He wrote as if a man stuck in a time which was not his own. Be that in the past, as with his "Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court" [which I loved as a youth] or in his side-ways admonishment of those who practiced racism by writing "Huckleberry Finn" foreshadowing the future of America's civil rights movement. Remember now, women did not even have the right to vote at the time he was alive and black men were still being denied their vote by Poll Taxes and other "tests" to see if they were literate. Twain, to me, took the illogical human traits he found and aired them out for all the world to examine, much like the "dirty laundry" my grandmother would talk about keeping out of the public.

People either loved him or hated him for his commentary through literature and articles. It is a harsh lesson to find your own traits condemned as false-thinking in a popular writer's stories. American society, as a whole, grew more nobel from the result. For sure, better able to laugh at themselves. Twain made us realize how serious we took our position as citizens of this "Grand Experiment" ~ the country without a monarchy ~ without a royal family to fawn on and envy. He would not live to see how 20th Century media presents the public with their idea of who is "royalty" -- the Kennedys, the movie stars, the sports stars. Wonder what he would say today.

It is our intention to use the web to introduce Twain's writings ~ including those where he went to other countries and wrote back his impressions. With no TV, no radio and no big-time movies going on yet, eloquent and prolific writers and speakers such as Mark Twain, Ambrose Bierce, Bret Harte and Jack London all caught the attention of the reading American public who were all anxious for stories from "far away lands." We will serialize them, if you will. We invite you check back to see what we've posted.

Roughing It & TE Tales

The Music

Millington & McCluskey's Band furnished the music for the Sanitary Ball on Thursday night, and also for the Odd Fellow's Ball the other evening in Gold Hill, and the excellence of the article was only equalled by the industry and perseverance of the performers. We condsider that the man who can fiddle all through one of those Virginia reels without losing his grip, may be depended upon in any kind of emergency.

More Ghosts

Are we to be scared to death every time we venture into the street? May we be allowed to go quietly about our business, or are we to be assailed at every corner by fearful apparitions. As we were plodding home at the ghostly hour last night, thinking about the haunted house humbug, we were suddenly riveted to the pavement in a paroxysm of terror by that blue and yellow phantom who watches over the destinies of the shooting gallery, this side of the International. Seen in daylight, placidly reclining against his board in the doorway, with his blue coat, and his yellow pants, and his high boots, and his fancy hat, just lifted from his head, he is rather an engaging youth, than otherwise; but at dead of night, when he pops out his pallid face at you by candle light, and stares vacantly upon you with his uplifted hat and the eternal civility of his changeless brow, and the ghostliness of his general appearance heightened by that grave-stone inscription over his stomach, "to-day shooting for chickens here," you are apt to think of spectres starting up from behind tomb-stones, and you weaken accordingly--the cold chills creep over you--our hair stands on end--you reverse your front, and with all possible alacrity, you change your base.

Sad Accident

We learn from Messrs. Hatch & Bro., who do a heavy business in the way of supplying this market with vegetables, that the rigorous weather accompanying the late storm was so severe on the mountains as to cause a loss of life in several instances. Two sacks of sweet potatoes were frozen to death on the summit, this side of Strawberry. The verdict rendered by the coroner's jury was strictly in accordance with the facts.

Our Stock Remarks

Owing to the fact that our stock reporter attended a wedding last evening, our report of transactions in that branch of robbery and speculation is not quite as complete and satisfactory as usual this morning. About eleven o'clock last night the aforesaid remarker pulled himself up stairs by the banisters, and stumbling over the stove, deposited the following notes on our table, with the remark: "S(hic)am, just 'laberate this, w(hic)ill, yer?" We said we would, but we couldn't. If any of our readers think they can, we shall be pleased to see the translation. Here are the notes: "Stocks brisk, and Ophir has taken this woman for your wedded wife. Some few transactions have occurred in rings and lace veils, and at figures tall, graceful and charming. There was some inquiry late in the day for parties who would take them for better OR for worse but there were few offers. There seems to be some depression in this stock. We mentioned yesterday that our Father which art in heaven. Quotations of lost reference, and now I lay me down to sleep," &c., &c., &c.

[Editor's Note: We figure Twain is talking about Dan DeQuille here.]

At Home

Judge Brumfield's nightmare--the Storey county delegation--have straggled in, one at a time, until they are all at home once more. Messrs. Mills, Mitchell, Meagher and Minneer returned several days ago, and we had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Davenport, also, yesterday. We do not know how long the latter gentleman has been here, but we offer him the unlimited freedom of the city, anyhow. Justice to a good representative is justice, you know, whether it be tardy or otherwise.

Thrilling Romance

On our first page, to-day, will be found the opening chapters of a thrilling tale, entitled "An Act to amend and supplemental to an Act to provide for Assessing and Collecting County and Territorial Revenue." This admirable story was written especially for the columns of this paper by several distinguished authors. We have secured a few more productions of the same kind, at great expense, and we design publishing them in their regular order. Our readers will agree with us that it will redound considerably to their advantage to read and preserve these documents.

Amazing Hot Springs

Eds. Enterprise: I have overstepped my furlough a full week - but then this is a pleasant place to pass one's time. These springs are ten miles from Virginia, six or seven from Washoe City and twenty from Carson. They are natural - the devil boils the water, and the white steam puffs up out of the crevices in the earth, along the summits of a series of low mounds extending in an irregular semicircle for more than a mile. The water is impregnated with a dozen different minerals each one of which smells viler than its fellow, and the sides of the springs are embellished with very pretty particolored incrustations deposited by the water. From one spring the boiling water is ejected a foot or more by the infernal force at work below, and in the vicinity of all of them one can hear a constant rumbling and surging, somewhat resembling the noises peculiar to a steamboat in motion hence the name.

Blown Down

At sunset yesterday, the wind commenced blowing after a fashion to which a typhoon is mere nonsense, and in a short time the face of heaven was obscured by vast clouds of dust all spangled over with lumber, and shingles, and dogs and things. There was no particular harm in that, but the breeze soon began to work damage of a serious nature. Thomas Moore's new frame house on the east side of C street, above the Court House, was blown down, and the fire-wall front of a one story brick building higher up the street was also thrown to the ground. The latter house was occupied as a store by Mr. Heldman, and owned by Mr. Felton. The storm was very severe for a while, and we shall not be surprised to hear of further destruction having been caused by it. The damage resulting to Mr. Heldman's grocery store, amounts to $2,200.

Stockbroker's Prayer

Our father Mammon who art in the Comstock, bully is thy name; let thy dividends come, and stock go up, in California as in Washoe. Give us this day our daily commissions; forgive us our swindles as we hope to get even on those who have swindled us. Unlead--us not into temptation of promising wild cat; deliver us from lawsuits; for thine is the main Comstock, the black sulphurets and the wire silver, from wallrock to wall-rock, you bet!

Valuable Horse

We have heard of thieves becoming so inclined to pilfer as to steal a red hot stove, but that isn't a circumstance to what we witnessed on C street yesterday, viz: the attempted theft of a cold one by a horse. Some of our light-fingered gentry should purchase that animal immediately. The gentleman who was astride him was busily engaged in conversation, when the horse, espying some stoves neatly stuffed with hay nearby, and being voraciously inclined, soon buried his head in one of them up to his eyes; but in attempting to remove his head from the stove aforesaid, which was a very large one, he found that it had got him. Upon making this discovery, he immediately began describing various geometrical figures through the crowd such as triangles, squares and circles forwards, and arcs etc., backwards - the stove still clinging firmer to his nose. But spying a policeman, he all at once seemed to have come to the conclusion that instead of the stove having him he had got the stove, and away he bounded with his unwilling rider at a fearful speed. Fortunately the violent plunging of the animal soon disarranged the stove, or we might have had a sad accident to record.

Report from Nevada's Constitutional Convention

EDS. ENTERPRISE: This has been a busy week--a notable and a historical week--and the only one which has yet passed over this region, perhaps, whose deeds will make any important stir in the outside world. Some dozens of people in America have heard of Nevada Territory (which they vaguely understand to be in Virginia City, though they have no definite idea as to where Virginia City is) as the place which sends silver bricks to the Sanitary fund; and some other dozens have heard of Washoe, without exactly knowing whether the name refers to the Northwest passage or to the source of the Nile--but when it is shouted abroad through the land that a new star has risen on the flag--a new State born to the Union--then the nation will wake up for a moment and ask who we are and where we came from. They will also ascertain that the new acquisition is called Nevada; they will find out its place on the map, and always recollect afterwards, in a general way, that it is in North America; they will see at a glance that Nevada is not in Virginia City and be surprised at it; they will behold that neither is it in California, and will be unable to comprehend it; they will learn that our soil is alkali flats and our shrubbery sage-brush, and be as wise as they were before; their mouths will water over statistics of our silver bricks, and verily they will believe that God createth silver in that form. This week's work is the first step toward giving the world a knowledge of Nevada, and it is a giant stride, too, for it will provoke earnest inquiry. Immigration will follow, and wild-cat advance.

This Convention of ours is well worth being proud of. There is not another commonwealth in the world, of equal population, perhaps, that could furnish the stuff for its fellow. I doubt if any Constitutional Convention ever officiated at the birth of any State in the Union which could boast of such a large proportion of men of distinguished ability, according to the number of its members, as is the case with ours. There are thirty-six delegates here, and among them I could point out fifteen who would rank high in any community, and the balance would not be second rate in most Legislatures. There are men in this body whose reputations are not local, by any means--such as Governor Johnson, Wm. M. Stewart, Judge Bryan, John A. Collins, N. A. H. Ball, General North and James Stark, the tragedian. Such a constellation as that ought to shed living light upon our Constitution. General North is President of the Convention; Governor Johnson is Chairman of the Legislative Committee--one of the most important among the Standing Committees, and one which has to aid in the construction of every department of the Constitution; Mr. Ball occupies his proper place as Chairman of the Committee on Finance, State Debt, etc.; the Judiciary Committee is built of sound timber, and is hard to surpass; it is composed of Messrs. Stewart, Johnson, Larrowe and Bryan.

We shall have a Constitution that we need not be ashamed of, rest assured; but it will not be framed in a week. Every article in it will be well considered and freely debated upon.

And just here I would like to know if it would not be as well to get up a constitutional silver brick or so, and let the Sanitary fund rest a while. It would cost at least ten thousand dollars to put this Convention through in anything approaching a respectable style; yet the sum appropriated by the Legislature for its use was only $3,000, and the scrip for it will not yield $1,500. The new State will have to shoulder the present Territorial debt of $90,000, but it seems to me we might usher her into the world without adding to this an accouchement fee--so to speak--of ten or fifteen thousand more. Why, the Convention is so poor that it cannot even furnish newspapers for its members to read; kerosene merchants hesitate to afford it light; unfeeling draymen who haul wood to the people, scorn its custom; it elected official reporters, and for two days could negotiate no desks for them to write on: it confers upon them no spittoons, to this day; in fact, there is only one spittoon to every 7 members and they furnish their own fine-cut into the bargain; in my opinion there are not inkstands enough to go around, or pens either, for that matter; Col. Youngs, Chairman of the Committee on Ways and Means (to pay expenses), has gone blind and baldheaded, and is degenerating into a melancholy lunatic; this is all on account of his financial troubles; it all comes of his tireless efforts to bullyrag a precarious livelihood for the Convention out of Territorial scrip at forty-one cents on the dollar. Will ye see him die, when fifty-nine cents would save him? I wish I could move the Convention up to Virginia, that you might see the Delegates worried, and business delayed or brought to a standstill every hour in the day by the eternal emptiness of the Treasury. Then would you grow sick, as I have done, of hearing members caution each other against breeding expense. I begin to think I don't want the Capital at Virginia if this financial distress is always going to haunt us. Now, I had forgotten until this moment that all these secrets about the poverty of the Convention treasury, and the inoffensive character of Territorial scrip, were revealed to the house yesterday by Colonel Youngs, with a feeling request that the reporters would keep silent upon the subject, lest people abroad should smile at us. I clearly forgot it--but it is too late to mend the matter now.

Hon. Gordon N. Mott is in town, and leaves with his family for San Francisco to-morrow. He proposes to start to Washington by the steamer of the 13th.

Mr. Lemmon's little girl, two years old, had her thigh bone broken in two places this afternoon; she was run over by a wagon. Dr. Tjader set the limb, and the little sufferer is doing as well as could be expected under the circumstances.

I used to hear Governor Johnson frequently mentioned in Virginia as a candidate for the United States Senate from this budding State of ours. He is not a candidate for that or any other office, and will not become one. I make this correction on his own authority, and, therefore, the various Senatorial aspirants need not be afraid to give it full credence.

Messrs. Pete Hopkins and A. Curry have compromised with me, and there is no longer any animosity existing on either side. They were a little worried at first, you recollect, about that thing which appeared recently (I think it was in the Gold Hill News), concerning an occurrence which has happened in the great pine forest down there at Empire.

We sent our last report to you by our stirring official, Gillespie, Secretary of the Convention. I thought that might account for you not getting it, in case you didn't get it, you know. ~ MARK TWAIN

Report from Carson: A Saturday Night Dance

EDS. ENTERPRISE: I feel very much as if I had just awakened out of a long sleep. I attribute it to the fact that I have slept the greater part of the time for the last two days and nights. On Wednesday, I sat up all night, in Virginia, in order to be up early enough to take the five o'clock stage on Thursday morning. I was on time. It was a great success. I had a cheerful trip down to Carson, in company with that incessant talker, Joseph T. Goodman. I never saw him flooded with such a flow of spirits before. He restrained his conversation, though, until we had traveled three or four miles, and were just crossing the divide between Silver City and Spring Valley, when he thrust his head out of the dark stage, and allowed a pallid light from the coach lamp to illuminate his features for a moment, after which he returned to darkness again, and sighed and said, "Damn itl" with some asperity. I asked him who he meant it for, and he said, "The weather out there." As we approached Carson, at about half past seven o'clock, he thrust his head out again, and gazed earnestly in the direction of that city--after which he took it in again, with his nose very much frosted. He propped the end of that organ upon the end of his finger, and looked down pensively upon it--which had the effect of making him appear cross-eyed--and remarked, "O. damn it!" with great bitterness. I asked him what he was up to this time, and he said, "The cold, damp fog--it is worse than the weather." This was his last. He never spoke again in my hearing. He went on over the mountains, with a lady fellow-passenger from here. That will stop his clatter, you know, for he seldom speaks in the presence of ladies.

In the evening I felt a mighty inclination to go to a party somewhere. There was to be one at Governor J. Neely Johnson's, and I went there and asked permission to stand around awhile. This was granted in the most hospitable manner, and visions of plain quadrilles soothed my weary soul. I felt particularly comfortable, for if there is one thing more grateful to my feelings than another, it is a new house--a large house, with its ceilings embellished with snowy mouldings; its floors glowing with warm-tinted carpets; with cushioned chairs and sofas to sit on, and a piano to listen to; with fires so arranged that you can see them, and know that there is no humbug about it; with walls garnished with pictures, and above all, mirrors, wherein you may gaze, and always find something to admire, you know. I have a great regard for a good house, and a girlish passion for mirrors. Horace Smith, Esq., is also very fond of mirrors. He came and looked in the glass for an hour, with me. Finally, it cracked--the night was pretty cold--and Horace Smith's reflection was split right down the centre. But where his face had been, the damage was greatest--a hundred cracks converged from his reflected nose, like spokes from the hub of a wagon wheel. It was the strangest freak the weather has done this Winter. And yet the parlor seemed very warm and comfortable, too.

About nine o'clock the Unreliable came and asked Gov. Johnson to let him stand on the porch. That creature has got more impudence than any person I ever saw in my life. Well, he stood and flattened his nose against the parlor window, and looked hungry and vicious--he always looks that way--until Col. Musser arrived with some ladies, when he actually fell in their wake and came swaggering in, looking as if he though he had been anxiously expected. He had on my fine kid boots, and my plug hat and my white kid gloves (with slices of his prodigious hands grinning through the bursted seams), and my heavy gold repeater, which I had been offered thousands and thousands of dollars for, many and many a time. He took these articles out of my trunk, at Washoe City, about a month ago, when we went out there to report the proceedings of the Convention. The Unreliable intruded himself upon me in his cordial way and said, "How are you, Mark, old boy? when d'you come down? It's brilliant, ain't it? Appear to enjoy themselves, don't they? Lend a fellow two bits, can't you?" He always winds up his remarks that way. He appears to have an insatiable craving for two bits.

The music struck up just then, and saved me. The next moment I was far, far at sea in a plain quadrille. We carried it through with distinguished success; that is, we got as far as "balance around," and "halt-a-man-left," when I smelled hot whisky punch, or something of that nature. I tracked the scent through several rooms, and finally discovered the large bowl from whence it emanated. I found the omnipresent Unreliable there, also. He set down an empty goblet, and remarked that he was diligently seeking the gentlemen's dressing room. I would have shown him where it was, but it occurred to him that the supper table and the punch-bowl ought not to be left unprotected; wherefore, we staid there and watched them until the punch entirely evaporated. A servant came in then to replenish the bowl, and we left the refreshments in his charge. We probably did wrong, but we were anxious to join the hazy dance. The dance was hazier than usual, after that. Sixteen couples on the floor at once, with a few dozen spectators scattered around, is calculated to have that effect in a brilliantly lighted parlor, I believe. Everything seemed to buzz, at any rate. After all the modern dances had been danced several times, the people adjourned to the supper-room. I found my wardrobe out there, as usual, with the Unreliable in it. His old distemper was upon him: he was desperately hungry. I never saw a man eat as much as he did in my life. I have the various items of his supper here in my note-book. First, he ate a plate of sandwiches; then he ate a handsomely iced poundcake; then he gobbled a dish of chicken salad; after which he ate a roast pig; after that, a quantity of blancmange; then he threw in several glasses of punch to fortify his appetite, and finished his monstrous repast with a roast turkey. Dishes of brandy-grapes, and jellies, and such things, and pyramids of fruits, melted away before him as shadows fly at the sun's approach. I am of the opinion that none of his ancestors were present when the five thousand were miraculously fed in the old Scriptural times. I base my opinion upon the twelve baskets of scraps and the little fishes that remained over after that feast. If the Unreliable himself had been there, the provisions would just about have held out, I think.

After supper, the dancing was resumed, and after a while, the guests indulged in music to a considerable extent. Mrs. J. sang a beautiful Spanish song; Miss R., Miss T., Miss P., and Miss S., sang a lovely duet; Horace Smith, Esq., sang "I'm sitting on the stile, Mary," with a sweetness and tenderness of expression which I have never heard surpassed; Col. Musser sang "From Greenland's Icy Mountains" so fervently that every heart in that assemblage was purified and made better by it; Mrs. T. and Miss C., and Mrs. T. and Mrs. G. sang "Meet me by moonlight alone" charmingly; Judge Dixson sang "O. Charming May" with great vivacity and artistic effect; Joe Winters and Hal Clayton sang the Marseilles Hymn in French, and did it well; Mr. Wasson sang "Call me pet names" with his usual excellence ( Wasson has a cultivated voice, and a refined musical taste, but like Judge Brumfield, he throws so much operatic affectation into his singing that the beauty of his performance is sometimes marred by it--I could not help noticing this fault when Judge Brumfield sang "Rock me to sleep, mother"); Wm. M. Gillespie sang "Thou hast wounded the spirit that loved thee," gracefully and beautifully, and wept at the recollection of the circumstance which he was singing about. Up to this time I had carefully kept the Unreliable in the background, fearful that, under the circumstances, his insanity would take a musical turn; and my prophetic soul was right; he eluded me and planted himself at the piano; when he opened his cavernous mouth and displayed his slanting and scattered teeth, the effect upon that convivial audience was as if the gates of a graveyard, with its crumbling tombstones, had been thrown open in their midst; then he shouted something about he "would not live alway"---and if I ever heard anything absurd in my life, that was it. He must have made up that song as he went along. Why, there was no more sense in it, and no more music, than there is in his ordinary conversation. The only thing in the whole wretched performance that redeemed it for a moment, was something about "the few lucid moments that dawn on us here." That was all right; because the "lucid moments" that dawn on that Unreliable are almighty few, I can tell you. I wish one of them would strike him while I am here, and prompt him to return my valuables to me. I doubt if he ever gets lucid enough for that, though. After the Unreliable had finished squawking, I sat down to the piano and sang--however, what I sang is of no consequence to anybody. It was only a graceful little gem from the horse opera.

At about two o'clock in the morning the pleasant party broke up and the crowd of guests distributed themselves around town to their respective homes; and after thinking the fun all over again, I went to bed at four o'clock. So, having been awake forty-eight hours, I slept forty-eight, in order to get even again, which explains the proposition I began this letter with.

Yours, dreamily,

MARK TWAIN

Grand Ball at La Plata

The Sanitary Ball at La Plata Hall on Thursday night [January 8, 1863] was a very marked success, and proved beyond the shadow of a doubt, the correctness of our theory, that ladies never fail in the undertakings of this kind. If there had been about two dozen more people there, the house would have been crowded--as it was, there was room enough on the floor for the dancers, without trespassing on their neighbors' corns. Several of those long, trailing dresses, even, were under fire in the thickest of the fight for six hours, and came out as free from rips and rents as they were when they went in. Not all of them, though.

We recollect a circumstance in point. We had just finished executing one of those inscrutable figures of the plain quadrille; we were feeling unusually comfortable, because we had gone through the performance as well as anybody could have done it, except that we had wandered a little toward the last; in fact we had wandered out of our own and into somebody else's set--but that was a matter of small consequence, as the new locality was as good as the old one, and we were used to that sort of thing anyhow. We were feeling comfortable, and we had assumed an attitude--we have a sort of talent for posturing-- pensive attitude, copied from the Colossus of Rhodes,-- when the ladies were ordered to the centre. Two of them got there, and the other two moved off gallantly, but they failed to make the connection. They suddenly broached to under full headway, and there was a sound of parting canvas. Their dresses were anchored under our boots, you know. It was unfortunate, but it could not be helped. Those two beautiful pink dresses let go amidships, and remained in a ripped and damaged condition to the end of the ball. We did not apologize, because our presence of mind happened to be absent at the very moment that we had the greatest need of it. But we beg permission to do so now.

An excellent supper was served in the large dining-room of the new What Cheer House on B street. We missed it there, somewhat. We were not accompanied by a lady, and consequently we were not elibible to a seat at the first table. We found out all about that at the Gold Hill ball, and we had intended to be all prepared for this one. We engaged a good many young ladies last Tuesday to go with us, thinking that out of the lot we should certainly be able to secure one, at the appointed time, but they all seemed to have got a little angry about something—nobody knows what, for the ways of women are past finding out. They told us we had better go and invite a thousand girls to go to the ball. A thousand. Why, it was absurd. We had no use for a thousand girls. A thou--but those girls were as crazy as loons. In every instance, after they had uttered that pointless suggestion, they marched magnificently out of their parlors---and if you will believe us, not one of them ever recollected to come back again. Why,it was the most unaccountable experience we had ever heard of. We never enjoyed so much solitude in so many different places, in one evening before. But patience has its limits; we finally got tired of that arrangement--and at the risk of offending some of those girls, we stalked off to the Sanitary Ball alone-- without a virgin, out of that whole litter. We may have done wrong--we probably did do wrong to disappoint those fellows in that kind of style--but how could we help it? We couldn't stand the temperature of those parlors more than an hour at a time: it was cold enough to freeze out the heaviest stock-holder on the Gould & Curry's books.

However, as we remarked before, everybody spoke highly of the supper, and we believe they meant what they said. We are unable to say anything in the matter from personal knowledge, except that the tables were arranged with excellent taste, and more than abundantIy supplied, and everything looked very beautiful, and very inviting, also, but then we had absorbed so much cold weather in those parlors, and had so much trouble with those girls, that we had no appetite left. We only eat a boiled ham and some pies, and went back to the ball room. There were some very handsome cakes on the tables, manufactured by Mr. Slade, and decorated with patriotic mottoes, done in fancy icing. All those who were happy that evening, agreed that supper was superb.

After supper the dancing was jolly. They kept it up till four in the morning, and the guests enjoyed themselves excessively. All the dances were performed, and the bill of fare wound up with a new style of plain quadrille called a medley, which involved the whole list. It involved us also. But we got out again--and we staid out, with great sagacity. But speaking of plain quadrilles reminds us of another new one--the Virginia reel. We found it a very easy matter to dance it, as long as we had thirty of forty lookers-on to prompt us. The dancers were formed in two long ranks, facing each other, and the battle opens with some light skirmishing between the pickets, which is gradually resolved into a general engagement along the whole line: after that, you have nothing to do but stand by and grab every lady that drifts within reach of you, and swing her. It is very entertaining, and elaborately scientific also; but we observed that with a partner who had danced it before, we were able to perform it rather better than the balance of the guests.

Altogether, the Sanitary Ball was a remarkably pleasant party, and we are glad that such was the case--for it is a very uncomfortable ask to be obliged to say harsh things about entertainments of this kind. At the present writing we cannot say what the net proceeds of the ball will amount to, but they will doubtless reach quite a respectable figure--say $400. -- Mark Twain

The Pony Express

In a little while all interest was taken up in stretching our necks and watching for the "pony-rider"--the fleet messenger who sped across the continent from St. Joe to Sacramento, carrying letters nineteen hundred miles in eight days! Think of that for perishable horse and human flesh and blood to do! The pony-rider was usually a little bit of a man, brimful of spirit and endurance. No matter what time of the day or night his watch came on, and no matter whether it was winter or summer, raining, snowing, hailing, or sleeting, or whether his "beat" was a level straight road or a crazy trail over mountain crags and precipices, or whether it led through peaceful regions or regions that swarmed with hostile Indians, he must be always ready to leap into the saddle and be off like the wind! There was no idling-time for a pony-rider on duty. He rode fifty miles without stopping, by daylight, moonlight, starlight, or through the blackness of darkness--just as it happened. He rode a splendid horse that was born for a racer and fed and lodged like a gentleman; kept him at his utmost speed for ten miles, and then, as he came crashing up to the station where stood two men holding fast a fresh, impatient steed, the transfer of rider and mail-bag was made in the twinkling of an eye, and away flew the eager pair and were out of sight before the spectator could get hardly the ghost of a look. Both rider and horse went "flying light." The rider's dress was thin, and fitted close; he wore a "roundabout," and a skull-cap, and tucked his pantaloons into his boot-tops like a race-rider. He carried no arms--he carried nothing that was not absolutely necessary, for even the postage on his literary freight was worth five dollars a letter. He got but little frivolous correspondence to carry--his bag had business letters in it mostly. His horse was stripped of all unnecessary weight, too. He wore light shoes, or none at all. The little flat mail-pockets strapped under the rider's thighs would each hold about the bulk of a child's primer. They held many and many an important business chapter and newspaper letter, but these were written on paper as airy and thin as goldleaf, nearly, and thus bulk and weight were economized. The stage-coach traveled about a hundred to a hundred and twenty-five miles a day (twenty-four hours), the pony-rider about two hundred and fifty. There were about eighty pony-riders in the saddle all the time, night and day, stretching in a long, scattering procession from Missouri to California, forty flying eastward, and forty toward the west, and among them making four hundred gallant horses earn a stirring livelihood and see a deal of scenery every single day in the year.

We had had a consuming desire, from the beginning, to see a pony-rider, but somehow or other all that passed us and all that met us managed to streak by in the night, and so we heard only a whiz and a hail, and the swift phantom of the desert was gone before we could get our heads out of the windows. But now we were expecting one along every moment, and -- would see him in broad daylight.

Presently the driver exclaims:

HERE HE COMES !

Every neck is stretched further, and every eye strained wider. Away across the endless dead level of the prairie a black speck appears against the sky, and it is plain that it moves. Well, I should think so! In a second or two it becomes a horse and rider, rising and falling, rising and falling--sweeping toward us nearer and nearer--growing more and more distinct, more and more sharply defined--nearer and still nearer, and the flutter of the hoofs comes faintly to the ear--another instant a whoop and a hurrah from our upper deck, a wave of the rider's hand, but no reply, and man and horse burst past our excited faces, and go swinging away like a belated fragment of a storm!

So sudden is it all, and so like a flash of unreal fancy, that but for the flake of white foam left quivering and perishing on a mail-sack after the vision had flashed by and disappeared, we might have doubted whether we had seen any actual horse and man at all, maybe. --Mark Twain

The Great American Desert

On the nineteenth day we crossed the Great American Desert--forty memorable miles of bottomless sand, into which the coach wheels sunk from six inches to a foot. We worked our passage most of the way across. That is to say, we got out and walked. It was a dreary pull and a long and thirsty one, for we had no water. From one extremity of this desert to the other, the road was white with the bones of oxen and horses. It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that we could have walked the forty miles and set our feet on a bone at every step! The desert was one prodigious grave-yard. And the log-chains, wagon tires and rotting wrecks of vehicles were almost as thick as the bones. I think we saw log-chains enough rusting there in the desert to reach across any state in the Union. Do not these relics suggest something of an idea of the fearful suffering and privation the early emigrants to California endured? -- Mark Twain

Musings of Mark Twain

We keep losing all the world's great authors. Chaucer is dead, and so is Milton and so is Shakespeare, and I am not feeling very well myself.

I have had a great many birthdays in my time. I remember the first one very well, and 1 always think of it with indignation; unaesthetic, triumviral. No proper preparation was made; nothing really ready why the cradle wasn't white washed. I hadn't any hair; I hadn't any teeth, I hadn't any clothes, I had to go to my first banquet dressed like that.

Everybody came swarming in, it was the merest little bit of a village in the backwoods of Missouri, where nothing ever happened and the people were all interested they all came why I came to the nearest thing to being a real event that had happened in that village in more than two years.

Now the world, it seems, has risen up rejoicing. I have had many honors conferred upon me, but I deserved them all.

I am glad to be back here in Hannibal, in view of the honor. I stepped ashore with the feeling of one who returns out of a dead and gone generation. I climbed Holidays Hill to get a comprehensive view. The whole town lay spread out below me. The New houses did not affect the older picture I had, the older picture in my mind, Hannibal, as it was. I experienced emotions that I had never expected. I was profoundly moved ....I said, So Many of the people I once knew in this tranquil refuge of my childhood are now in heaven; some, I trust, are in the other place."

Living in Hannibal, on the banks of the Mississippi, was a paradise - it was a simple, simple life, and there was nothing of this age of modern civilization here at all.

There was no crime. Merely little things like pillaging orchards and watermelon patches and breaking the Sabbath - we didn't break the Sabbath often enough to signify - once a week perhaps. We were good boys, we were good Presbyterian boys - when the weather was doubtful; when it was fair, we did wander a little from the fold.

School days - we look back upon them regretfully because we have forgotten our punishments at school, and how we grieved when our marbles were lost and our kites destroyed - we have forgotten all the sorrows and privations of that canonized epoch and remember only its orchards robberies, its wooden sword pageants, and its fishing holidays.

I do have some good advice for the young people here - always obey your parents, when they are present. I learned that by experience. Parents think they know better than you do, and I think it is wise to humor that superstition. I never let schooling interfere with my education. --Mark Twain

Tales Of A Treacherous Ride

Editors Enterprise: The trip from Virginia to Carson by Messrs. Carpenter & Hoog's stage is a pleasant one... Our driver was a very companionable man, though, and this was a happy circumstance for me, because, being drowsy and worn out, I would have gone to sleep and fallen overboard if he had not enlivened the dreary hours with his conversation.

Whenever I stopped coughing, and went to nodding, he always watched me out of the corner of his eye until I got to pithing in his direction, and then he would stir me up and inquire if I were asleep. If I said "No" (and I was apt to do that), he always said "it was a bully good thing for me that I wasn't, you know," and then went on to relate cheerful anecdotes of people who had got to nodding by his side when he wasn't noticing, and had fallen off and broken their necks. He said he could see those fellows before him now, all jammed and bloody and quivering in death's agony -- G'Iang! d--n that horse, he knows there's a parson and an old maid inside, and that's what makes him cut up so: I've saw him act jes' so more'n a thousand times!"

The driver always lent an additional charm to his conversation by mixing his horrors and his general information together in this way. "Now," said he, after urging his team at a furious speed down the grade for a while, plunging into deep bends in the road brimming with a thick darkness almost palpable to the touch, and darting out again and again on the verge of what instinct told me was a precipice, "Now, I seen a poor cuss -- but you're asleep again, you know, and you've rammed you head agin' my sidepocket and busted a bottle of nasty rotten medicine that I'm taking to the folks at the Thirty-five Mile House; do you notice that flavor? ain't it a ghastly old stench? The man that takes it down there don't live on anything else -- it's vittles and drink to him; anybody that ain't used to him can't go a-near him; he'd stun 'em -- he'd suffocate 'em; his breath smells like a graveyard after an earthquake -- you, Bob! I allow to skelp that ornery horse, yet, if he keeps on this way; you see he's been on the overland till about two weeks ago, and every stump he sees he cal'lates it's an Injun."

I was awake by this time, holding on with both hands and bouncing up and down just as I do when I ride a horseback. The driver took up the thread of his discourse and proceeded to soothe me again: "As I was saying, I see a poor cuss tumble off along here one night -- he was monstrous drowsy, and went to sleep when I'd took my eye off of him for a moment -- and he fetched up agin a boulder, and in a second there wasn't anything left of him but a promiscus pile of hash! It was moonlight, and when I got down an looked at him he was quivering like jelly, and sorter moaning to himself, like and the bones of his legs was sticking out through his pantaloons every which way, like that." (Here the driver mixed his fingers up after the manner of a stack of muskets, and illuminated them with the ghostly light of his cigar.) "He warn't in misery long though. In a minute an a half he was deader'n a smelt -- Bob! I say I'll cut that horse's throat if he stays on this route another week."

In this way the genial driver caused the long hours to pass sleeplessly away, and if he drew upon his imagination for his fearful histories, I shall be that last to blame him for it, because if they had taken a milder form I might have yielded to the dullness that oppressed me, and got my own bones smashed out of my hide in such a way as to render me useless forever after -- unless, perhaps, some one chose to turn me into account as an uncommon sort of hat-rack. --Mark Twain

Dead Indian Found in Water Tank

Of late the water with which this town is supplied by the Virginia and Gold Hill Water Company has been quite muddy owing to a cave having occurred in a tunnel which is their principal source of supply. The water did not look well nor taste well. This being the case, people were easily led to believe the story which yesterday got started and spread like wild-fire through the town that the dead and partially decomposed body of an Indian had been discovered in one of the large water tanks or reservoirs high up on the side of the mountain in the western suburbs of the town.

More than half of those who heard the report firmly believed it, and those who did not took delight in spreading the story, just for the fun of sickening their acquaintances. As the story traveled it grew, and at last it was said that in another tank two rotten dogs had been found. As these stories spread there was much vomiting throughout the town, particularly among the ladies. Not a few men also, if the truth is told, threw up thier breakfasts. In some houses the woman folks almost famished of thirst, while in others they procured ice and melted it for cooking and drinking purposes. To say water to a man was to see him turn up his nose and make a wry face. All the breweries and saloons did a land office business and the Dashaways and Good Templars looked as though they would not be able to stand firm much longer.

The Piutes heard that a red brother had been found drowned in one of the tanks, and about fifty of them charged up the mountain in search of the body. During their raid they tore the covers off the several tanks in spite of the remonstrances of Mr. Cody, foreman of the Water Company, and would not be satisfied till they had thoroughly prospected them, when they said: "White man heap tell um d-- n lies." After the red men left Mr. Cody had to go to work and repair damages by nailing down the planks forming the covers of the tanks, the openings into which are always kept locked. In short, the town was in a regular uproar, and the women and everybody that could get sight of Mr. Cody gave him particular fits. It was no use for him to deny the story. All knew they had been drinking dead Indian for the last ten days. They had tasted him and could not be fooled. Others had seen dog hair in the water and had tasted dog. Several had for some days observed floating on the water a peculiar scum and had been unable to account for it, but knew what it was now--it was Indian fat. Thus ran the talk throughout the city, and no wonder that the women vomited.

The fact is that all the tanks are kept tightly covered and locked and nothing at all has been found in the tanks, or has entered them, worse than the muddy water from one of the water tunnels. The muddieness of the water is caused by a cave in this tunnel, as we have said. To attempt to clear the tunnel of the dirt caved down would render the water almost thick with mud for a week or more, and water is now so scarce that they dare not undertake this, as it would leave no water for the town. The only remedy for this state of affairs is to use as much ice in the water comsumed as it can be made to melt.

Frightful Accident to Dan DeQuille

Our time-honored confrere, Dan, met with a disastrous accident, yesterday while returning from American City on a vicious Spanish horse, the result of which accident is that at the present writing he is confined to his bed and suffering great bodily pain. He was coming down the road at the rate of a hundred miles an hour (as stated in his will, which he made shortly after the accident,) and on turning a sharp corner he suddenly hove in sight of a horse standing square across the channel; he signalled for the starboard, and put his helm down instantly, but too late, after all he was swinging to port, and before he could straighten down, he swept like an avalanche against the transom of the strange craft; his larboard knee coming in contact with the rudderpost of the adversary, Dan was wrenched from his saddle and thrown some three hundred yards (according to his own statement made in his will, above mentioned, alighting upon solid ground, and bursting himself open from the chin to the pit of the stomach. His head was also caved in out of sight, and his hat was afterwards extracted in a bloody and damaged condition from between his lungs, he must have bounced end-for-end after he struck first, because it is evident he received a concussion from the rear that broke his heart; one of his legs was jammed up in his body nearly to his throat, and the other so torn and mutilated that it pulled out when they attempted to lift him into the hearse which we had sent to the scene of the disaster, under the general impression that he might need it; both arms were indiscriminately broken up until they were jointed like a bamboo; the back was considerably fractured and bent into the shape of a rail fence. Aside from these injuries, however, he sustained no other damage. They brought some of him home in the hearse and the balance on a dray. His first remark showed that the powers of his great mind had not been impaired by the accident, nor his profound judgment destroyed -- he said he wouldn't have cared a d--n if it had been anybody but himself. He then made his will, after which he set to work with that earnestness and singleness of purpose which have always distinguished him, to abuse the assemblage of anxious hashhouse proprieters who had called on business, and to repudiate their bills with his customary promptness and impartiaiity Dan may have exaggerated the above details in some respects, but he charged us to report them thus, and it is a source of genuine pleasure to us to have the opportunity of doing it. Our noble friend is recovering fast, and what is left of him will be around the Brewery again to day, just as usual.

A Gorgeous Scandal

Dr. May, of the International Hotel, has put into our hands the following documents, which will afford an idea of how infinitely mean some people can become when they get a chance. This firm of Read & Co., Bankers, 42 South Third street, Philadelphia, will do to travel — but not in Washoe, if we understand the peculiar notions of this people. The accompanying letter, circular, and certificate of stock were sent by Read & co. to Dr. May's nephew, Theodore E. Clapp, Esq., Postmaster at White Pigeon, Michigan. Through the Doctor, Mr. Clapp had learned a good deal about Washoe, and saw at a glance, of course, that a swindle was on foot which would not only cheat multitudes of the poorest classes of men in the States, but would go far toward destroying confidence in our mines and our citizens if permitted to succeed. He lost no time, therefore, in forwarding the villainous papers to Dr. May, and we are sure the people of the Territory are right heartily thankful to him for doing so.

The certificate of stock is a curiosity in the way of unblushing rascality. It does not state how many shares there are in the company, or what a share is represented by. It is a comprehensive arrangement—the company propose to mine all over Nevada Territory, adjoining California"! They are not partial to any particular mining district. They are going to "carry on" a general "gold and silver mining business"! — The untechnical, leather-headed thieves! The company is "to be" organized—at some indefinite period in the future—probably in time for the resurrection The company is "to be" incorporated orated "for the purpose of purchasing machinery" — they only organize a company in order to purchase machinery—the inference is, that they calculate to steal (he mine. And only to think—a man has only got to peddle forty of fifty of these certificates of stock for Mrssrs. Read & co. in order to become fearfully and wonderfully wealthy!—Or, as they eloquently put it, "By taking hold now, and assisting to raise the capital stock of this company, you have it within your grasp to place yourself [in] a way to receive a large income annually without spending one cent!" Oh, who wouldn't take hold now? Breathes there a man with soul so dead that he wouldn't take hold under such seductive circumstances? Scasely. Read & Co. want to get money—rather than miss, they will even grab at a paltry two-and-a-half piece—thus: "You can send in $2.50 at a timed Two and a half at a time, to buy shares in another Gould & Curry!

But the coolest, the soothingest, the roost refeshingest paragraph (to speak strongly) is that one which is stuck in at the bottom of the circular, with an air bout it which mutely says, "it's of no consequence, and scarcely worth mentioning, but then it will do to fill out the page with." The paragraph reads as follows: "N.B. — Subscribers can receive their dividends, as they fall due, at Messrs. Read & Co.'s Banking House, No. 42 South Third street, Philadelphia, or have them forwarded by express, of which all will be regularly notified!" We imagine we can see a denizen of some obscure western town walking with stately mien to the express office to get his regular monthly dividend; we imagine less fortunate people making way for him, and whispering together, "there goes old Thompson— owns ten shares in the People's God and Silver Mining Company—Lord! but he's rich! —He's going after his dividends now." And we imagine we see old Thompson and his regular dividends fail to connect. And finally, we imagine we see the envied Thompson jeered at by his same old neighbors as "the old fool who got taken in by the most palpable humbug of the century."

Read & Co.'s certificate of stock does not state how many shares there are in the company, or what a share is represented by.

Who is "Wm. Heffly, Esq., of San Francisco," who knows it all, and who has calmly waited for three years without once swerving from his purpose of "starting a mining company" as soon as he could become satisfied that quartz-mining was a permanent thing? Cautious scoundrel! You couldn't fool him into going into a highway robbery like tile "People's Gold and Silver Mining Company," he wrote those circulars and things, he was never a week in Washoe in his life, because we don't talk about "cap rocks in this country - that's a Pike's Peak phrase; and when we talk about "cab-rock," we never say it pays "$24 to the ton," or any other price; we don't crush wall-rock, as a general thing. There is no 'Washoe Mining District' in this Territory, and the President of the People's Company did a bully good thing when he "reserved the right to change the location of operations whenever he pleased. Mr. Heffly's knowledge of the prices of leading stocks here borders on the marvelous. He says Gould & Curry is worth "$5,000 per share." A "share" is three inches; but Gould & Curry don't sell at $20,000 a foot; he puts Ophir at $2,400 "per share"; now a "sharer of Ophir is one inch. All the other prices mentioned by Mr. Heffly are wrong, and never were right at any time, perhaps. In the items written by Mr. Heffly, and pretended to be clipped from the Bulletin and the Standard, he uses mining technicalities never uttered either by miners or newspaper men in this part of America. The only true statement in these documents is the one which reads -- "Therefore, in subscribing to the capital stock of this company, you are acting on a certainty, and taking no risk whatever." That is eminently so. You are acting on the certainty of being swindled, and so far from there being any risk about that result, is the deadest open and shut thing in the world.

Now this swindle ought to be well ventilated by the newspapers -- not that sound business men will ever be swindled by it, but the unsuspecting multitude, who yearn to grow suddenly rich, will assuredly have their slender purses drained by it. . . --Mark Twain

Wrong Man Tried for Murder: The China Trial

We were there yesterday, not because we were obliged to go, but just because we wanted to. The more we see of this aggravated trial the more profound does our admiration for it become. It has more faces than the moon has in a chapter of the almanac.

It commenced as an assassination; the assassinated man neglected to die, and they turned it into assault and battery; after this the victim did die, whereupon his murderers were arrested and tried yesterday for perjury; they convicted one Chinaman, but when they found out it was the wrong one, they let him go - and why they should have been so almighty particular is beyond our comprehension; then, in the afternoon, the officers went down and arrested Chinatown again for the same old offense, and put it in jail,- but what shape the charge will take this time no man can foresee: the chances are that it will be about a standoff between arson and robbing the mail.

Capt. White hopes to get the murderers of the Chinaman hung one of these days, and so do we, for that matter, but we do not expect anything of the kind. You see, these Chinamen sire all alike, and they cannot identify each other. They mean well enough, and they really show a disinterested anxiety to get some of their friends and relatives hung, but the same misfortune overtakes them every time: they make mistakes and get the wrong man, with unvarying accuracy.

With a zeal in behalf of justice which cannot be too highly praised, the whole Chinese population have accused each other of this murder, each in his regular turn. But fate is against them. They cannot tell each other apart. There is only one way to manage this thing with strict equity: hang the gentle Chinese promiscuously until justice is satisfied. --Mark Twain

A Bloody Massacre in Carson City

From Abram Curry, who arrived here yesterday afternoon from Carson, we have learned the following particulars concerning a bloody massacre which was committed in Ormbsy County the night before last. It seems that during the past six months a man named P. Hopkins, or Philip Hopkins, has been residing with his family in the old log house just to the edge of the great pine forest which lies between Empire City and Dutch Nick's.

The family consisted of nine children - five girls and four boys - the oldest of the group, Mary, being nineteen years old, and the youngest, Tommy, about a year and a half. Twice in the past two months Mrs. Hopkins, while visiting in Carson, expressed fears concerning the sanity of her husband, remarking that of late he had been subject to fits of violence, and that during the prevalence of one of these he had threatened to take her life. It was Mrs. Hopkins' misfortune to be given to exaggeration, however, and but little attention was paid to what she said. About ten o'clock on Monday evening Hopkins dashed into Carson on horseback, with his throat cut from ear to ear, and bearing in his hand a reeking scalp from which the warm smoking blood was still dripping, and fell in a dying condition in front of the Magnolia saloon.

Hopkins expired in the course of five minutes, without speaking. The long red hair of the scalp he bore marked it as that of Mrs. Hopkins. A number of citizens, headed by Sheriff Gasberie, mounted at once and rode down to Hopkins' house, where a ghastly scene met their gaze. The scalpless corpse of Mrs. Hopkins lay across the threshold, with her head split open and her right hand almost severed from the wrist. Near her head lay the ax with which the murderous deed had been committed. In one of the bedrooms six of the children were found, one in bed and the others scattered about the floor. They were all dead. Their brains had evidently been dashed out with a club, and every mark about them seemed to have been made with a blunt instrument.

The children must have struggled hard for their lives, as articles of clothing and broken furniture were strewn about the room in the utmost confusion. Julia and Emma, aged respectively fourteen and seventeen, were found in the kitchen, bruised and insensible, but it is thought their recovery is possible. The eldest girl, Mary, must have taken refuge, in her terror, in the garret, as her body was found there frightfully mutilated and the knife with which her wounds had been inflicted still sticking in her side. The two girls, Julia and Emma, who had recovered sufficiently to be able to talk yesterday morning, state that their father knocked them down with a billet of wood and stamped upon them. They think they were the first attacked.

They further state that Hopkins had shown evidence of derangement all day, but had exhibited no violence. He flew into a passion and attempted to murder them because they advised him to go to bed and compose his mind. Curry says Hopkins was about forty-five years of age, and was a native of Western Pennsylvania; he was always affable and polite, and until very recently we had never heard of his ill treating his family. He had been a heavy owner in the best mines of Virginia and Gold Hill, but when the San Francisco papers exposed the game of cooking dividends in order to bolster up our stocks, he grew afraid and sold out, and invested an immense amount in the Sprinq Valley Water Company of San Francisco. He was advised to do this by a relative of his, one of the editors of the San Francisco BULLETIN, who had suffered pecuniarily by the dividend cooking system as applied to the Dana Mining Company recently. Hopkins had not long ceased to own in the various claims on the Comstock lead, however, when several dividends were cooked on his newly acquired property, their water totally dried up, and Spring Valley stock went down to nothing. It is presumed that this misfortune drove him mad and resulted in his killing himself and the greater portion of his family.

The newspapers of San Francisco permitted this water company to go on borrowing money and cooking dividends, under cover of which cunning financiers crept out of the tottering concern, leaving the crash to come upon poor and unsuspecting stockholders, without offering to expose the villainy at work. We hope the fearful massacre detailed above may prove the saddest result of their silence. --Mark Twain

Dead Man Turns to Stone

A petrified shah was found some time ago in the mountains south of Gravelly Ford. Every limb and feature of the stone mummy was perfect, not even excepting the left leg, which had evidently been a wooden one during the lifetime of the owner - which lifetime, by the way, came to a close about a century ago, in the opinion of a savant who has examined the defunct.

The body was in a sitting position, and leaning against a huge mass of droppings; the attitude was pensive, the right thumb rested against the side of the nose; the left thumb partially supported the chin, the forefinger pressing the inner corner of the left eye, and drawing it partly open; the right eye closed, and the fingers of the right hand spread out. This strange freak of nature created a profound sensation in the vicinity, and our informant states that, by request, Judge Sewell at once proceeded to the spot and held an inquest on the body. The verdict was that "deceased came to his death from protracted exposure." --Mark Twain

Drunken Buggy Driver Kills Woman

Mrs. Mary Durning, who kept a lodging house on South C street, while out on the Geiger Grade for a drive last Sunday was thrown or jumped from the buggy in which she was riding and was killed. It is thought her neck was broken. She had been to the Miners' Union picnic, and after returning rode out on the grade with Dennis Crowley, who was under the influence of liquor, and was in no condition to manage a team. Somewhere in the neighborhood of the Sierra Nevada Crowley fell or was jolted out of the buggy, and it is supposed that, seeing herself left in the vehicle with the lines trailing on the ground and the team running, Mrs. Durning attempted to save herself by jumping out. Had she remained in the buggy she would have escaped, as the team finally brought up at the toll-house with neither buggy nor harness injured. The accident is supposed to have happened about 9 o'clock.

At 10 o'clock 2 Utah miner named Ike Haley found Crowley and Mrs. Duming lying in the road and sent word to the Polke Station. Chief Brown and others proceeded to the spot at once and found Crowley sitting upon the ground holding the lifeless form of Mrs. Durning, whose neck had been broken by the fall. Crowley at that time was too much intoxicated to give any intelligible account of the accident.

No one appears to know just how the accident occurred. Mrs. Durning was about 43 years of age and has two children - a boy, Frank, aged 16, and a daughter younger. --Mark Twain

How Mark Twain got his start in the newspaper business

Now in pleasanter days I had amused myself with writing letters to the chief paper of the Territory, the Virginia City Territorial Enterprise, and had always been surprised when they appeared in print. My good opinion of the editors has steadily declined; for it seemed to me that they might have found something better to fill up with than my literature. I had found a letter in rhe post office as I came home from the hillside, and finally I opened it. Eureka! (I never did know what Eureka meant, but it seems to be as proper a word to heave in as any when no other that sounds pretty offers.) It was a deliberate offer to me of Twenty-Five Dollars a week to come up to Virginia City and be city editor of the Enterprise.

I would have challenged the publisher in the "blind lead" days -- I wanted to fall down and worship him, now Twenty-Five Dollars a week -- it looked like bloated luxury -- a fortune -- a sinful and lavish waste of money. But my transports cooled when I thought of my inexperience and consequent unfitness for the position -- and straightway, on rap of this, my long array of failures rose up before me. Yet if I refused this place I must presently become dependent upon somebody for my bread, a thing necessarily distasteful to a man who had never experienced such a humiliation since he was thirteen years old. Not much to be proud of, since it is so common -- but then it was all I had to be proud of. So I was scared into being a city editor. I would have declined, Otherwise Necessity is the mother of "taking chances." I do not doubt that if, at that time, I had been offered a salary to translate the Talmud from the original Hebrew, I would have accepted -- albeit with diffidence and some misgivings -- and throw as much variety into it as I could for the money.

I went up to Virginia and entered upon my new vocation. I was a rusty looking city editor, I am free to confess -- coatless, slouch hat, blue woolen shirt, pantaloons stuffed into boot-tops, whiskered half down to the waist, and the universal navy revolver slung to my belt. But l secured a more Christian costume and discarded the revolver. I had never had occasion to kill anybody, nor ever felt a desire to do so, but had worn the thing in deference to popular sentiment, and in order that I mighr not, by its absence, be offensively conspicuous, and a subject of remark. But the other editors, and all the printers, carried revolvers. I asked the chief editor and proprietor (Mr. Goodman, I will call him, since it describes him as well as any name could do) for some instructions with regard to my duties and he told me to go all over town and ask all sorts of people all sorts of questions, make notes of the information gained, and write them out for publication. And he added:

"Never say 'We learn' so-and-so, or 'It is reported,' or 'It is rumored,' or 'We understand' so-and-so, but go to headquarters and get the absolute facts, and then speak out and say 'It is so-and-so.' Otherwise, people will not put confidence in your news. Unassailable certainty is the thing that gives a newspaper the firmest and most valuable reputation."

It was the whole thing in a nutshell; and to this day when I find a reporter commencing his article with "We understand," I gather a suspicion that he has not taken as much pains to inform himself as he ought to have done. I moralize well, but I did not always practice well when I was a city editor; I let fancy get the upper hand of fact too often when there was a dearth of news. I can never forget my first day's experience as a reporter. I wandered about town questioning everybody, boring everybody, and finding out that nobody knew anything. At the end of five hours my notebook was still barren. I spoke to Mr. Goodman. He said:

"Dan used to make a good thing out of the hay wagons in a dry time when there were no fires or inquests. Are there no hay wagons in from the Truckee? If there are, you might speak of the renewed activity and all that sort of thing, in the hay business, you know. It isn't sensational or exciting, but it fills up and looks business like."

I canvassed the city again and found one wretched old hay truck dragging in from the country. But I made affluent use of it. I multiplied it by sixteen, brought it into town from sixteen different directions, made sixteen separate items out of it, and got up such another sweat about hay as Virginia City had never seen in the world before.

This was encouraging. Two nonpareil columns had to be filled, and I was getting along. Presently, when things began to look dismal again, a desperado killed a man in a saloon and joy returned once more. I never was so glad over any mere trifle before in my life. I said to the murderer:

"Sir, you are a stranger to me, but you have done me a kindness this day which I can never forget. If whole years of gratitude can be to you any slight compensation, they shall be yours. I was in trouble and you have relieved me nobly and at a time when all seemed dark and drear. Count me your friend from this time forth, for I am not a man to forget a favor."

If I did not really say that to him I at least felt a sort of itching desire to do it. I wrote up the murder with a hungry attention to details, and when it was finished experienced one regret -- namely, that they had not hanged my benefactor on the spot, so that I could work him up too. --Mark Twain

Stories About Mark Twain

But First Came the Territorial Enterprise: A Paper is Born

In the very shadow of the High Sierra, in a drafty shack through whose chinks the December snowfall filtered to form miniature drifts along floor and windowsill, two bearded men assisted by an apprentice boy wrestled with a secondhand Washington printing press.

The patent furniture of the primeval instrument was cold. So were the chases holding the long columns of agate and brevier in at least an approximation of true alignment. The ink on the hand-activated inking roller had forgotten that it was ever fluid. Everything was gelid to the touch and the breath of the two frock-coated men turned white as they panted over their task. The cannon-ball stove in the corner, for all it glowed red with a fire of cottonwood logs, hardly made a dent in the Antarctic cold that enveloped the entire Territory of Western Utah.

The two men made frequent reference to a handy black bottle containing a sovereign remedy of the countryside, called valley tan; and the apprentice boy made mental notes to explore some day for himself its possibilities.

The two ancients also cursed with fearful and ornate profanity, drawing upon resources of the literary antiquities both Biblical and profane, upon the classical humanities, upon the Book of Mormon, and upon a surprising knowledge of anatomic possibilities both animal and human. They cursed Nevada by sections and quarter sections. And most of all they made special reservations in the permanent residential areas of hell for Richard M. Hoe, in far-off New York, who had devised the infernal contrivance with which they were contesting, and his brother Robert Hoe, who merchandised the artifact.

The accursed brothers Hoe conducted a well-established and highly profitable business in downtown Manhattan at the comer of Broom and Sheriff streets where they offered for sale all sorts of ingenious aids to printing: hand presses of the Washington plan, proofing machines, stitching and binding devices, type cases and such. But only hell itself, the two printers of Mormon Station were in accord, could have outshopped such a desperate devising as the one at hand; and back to the foundries and machine shops of hell they consigned the Hoes and all their works.

The elder and more proficient blasphemer, did he but know it, was merely getting in practice for an exercise in cursing some twenty years later which would become legendary throughout the entire West and elevate the technique of execration to realms of supernal artistry.

In desperation, the thwarted molders of the public mind poured Niagaras of valley tan into themselves and over the running parts of the machinery as a lubricant. Wasn't it an accepted fact that whisky was in the ink of the pioneer press both metaphorically and factually? And at length the machinery creaked into a reasonable facsimile of action, and the more sober partner was able to snatch from its inner economy the six column one sheet the first copy of the first newspaper ever to be printed in the howling wilderness of Nevada.

The logotype read, The Territorial Enterprise. Thus, in a mist both blasphemous and alcoholic, prophetic of things to come, was born the paper that was shortly to be the pattern and glass of frontier journalism everywhere, and eventually was to achieve immortality as one of the romantic properties of the Old American West.

Lacking the crystal ball of Mrs. Sandy Bowers, a seeress even at that moment headed for the same place as The Enterprise, thirty miles distant on the slopes of Mount Davidson, W.L.. Jernegan and Alfred James were unable to see the promise of things to come in their so perilously delivered child. The partners buttoned their frock coats across their chests against the elements and ran through the snow to the Stockade Bar to show the first copy of the paper to Isaac Roop, who happened to be in town from Susanville.

Other than the indomitable hanker of the frontier to set itself up in the pattern of the good life the pioneers had known back home, it is difficult at this remove to understand what motivated the seedy itinerants Jernegan and James to ferry Nevada's first newspaper bodily overland from Salt Lake by ox team and hang out their shingle in Mormon Station. The community, which was later to change its name to Genoa, as it remains to this day, numbered something fewer than two hundred permanent residents. It was a freighting station on the emigrant route to California, a staging depot where teamsters and draymen changed horses and oxen for the ascent of the Sierra on the way to Lake Tahoe, Strawberry, Sportsman's Hall, and, eventually, Hangtown.

Mormon Station needed a newspaper far less than it required a physician, a pharmacist, and an undertaker. It had a sufficiency of wheelwrights, farriers, and bartenders. A newspaper was at best a devising of metropolitan luxury; at worst, an economic folly. But just as every community in the land must, only a few years from now, have a railroad of its very own, so did every hamlet and crossroads in the West pant as the hart panteth for the water springs for its own newspaper. Jernegan and James were the men anointed to bring this consummation to Mormon Station on the evening of December 18, 1858.

Save by professional chroniclers of yesterday, Jernegan and James are forgotten now, but once, like the stout Cortez, they stood on a peak in Darien and a world spread itself before them. They were the prototype and archetype of the frontier printer, in soup stained frock coat and dented top hat, resolute, his breath perfumed with strong waters, type stick in one hand, the other on the stock of a belted gun, facing Indians, the wilderness, the opposition, creditors and hangover. O Pioneers!

Jernegan and James, according to Dan De Quille in later years, had been at something of a loss for a name for their paper and had written to a friend in the Mother Lode diggings of California, one Washington Wright, asking for suggestions. A return letter from Wright, brought to Mormon Station by Snowshoe Thompson, the universal postman, suggested that since the venture was a new enterprise in the then Territory of Western Utah, what could be more appropriate than The Territorial Enterprise?

Jernegan and James were delighted and invited everyone in the Stockade Bar to have something for their stomachs, and The Territorial Enterprise became the first of many papers of that name elsewhere in the land.

No self-respecting newspaper in those mannered days could come into being without a prospectus, and the partners lost no time in having one run up. It read: A JOURNAL FOR THE EASTERN SLOPE

The Undersigned very respectfully announce that they will commence on the first week of November next, 1858, at Carson City, Eagle Valley, the publication of a Weekly Independent Newspaper, entitled The Territorial Enterprise. It will industriously and earnestly be devoted to the advancement of everything pertaining to the beautiful country bounded on the West by the Sierra Nevadas and extending into and forming the Great Basin of the Continent...