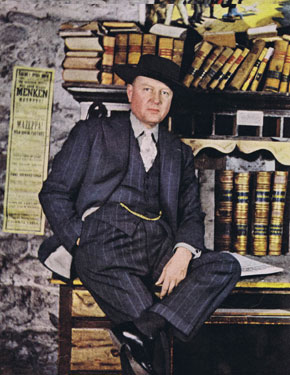

Lucius Beebe

Background of the Territorial Enterprise

Originally an aspiring poet, and always a tireless writer, Lucius Beebe gained notoriety for his brash journal articles about the thrill of high society life. Beebe turned out syndicated columns for an array of publications, largely dealing with his world travels and what he termed the "Café Society," an elite group of socialites he himself belonged to. In the 1950s he moved to Nevada with his partner, Charles Clegg. Beebe may have been drawn to the wild atmosphere of the Comstock, where drinking and open ribaldry were par for the course. But he was also interested in the newspaper made famous by Mark Twain, the Territorial Enterprise. He and Clegg bought the paper shortly after arriving in Virginia City. Even after selling the paper in 1960, Beebe and Clegg kept a residence in Nevada while continuing world travels.

History of the TE

A Biographical Sketch

Lucius Morris Beebe was born on December 9, 1902, at Wakefield, Massachusetts, near Boston, the son of Junius and Eleanor (Merrick) Beebe. The first Beebes had come to America in 1650 and had prospered in their various ventures, so that by 1750 the descendants, scattered throughout New England but concentrated chiefly in Somerset County, Massachusetts, were landed and wealthy men of property. Lucius' father was no exception to this tradition, and during his lifetime was head of his own large leather business in Boston, president of the Wakefield Trust Company and of the Brockton Gas Company, director of the Atlantic National Bank of Boston, and director of the Mutual Chemical Company of New York. The Beebe farm at Wakefield was a sizable 140 acres, and it was here and, during the winter months, in Boston that the "Boy Beebe" grew up.

Beebe's early schooling was peripatetic: from the North Ward School in Wakefield he went at the age of fifteen to St. Marks in Southboro to be sent home, almost instanter, for a dynamiting episode comparable to the one he describes in "Wakefield: The Town That Will Never Forget Me;" he then went to the Berkshire School in Sheffield and was in due course returned for having discovered alcohol in Boston and bringing it, Beebe-Prometheus, to Berkshire; his third prep school was the Roxbury School, in Chesire, Connecticut, which he survived to enter Yale in 1922. At Yale he would have graduated with the class of 1926 -- with Peter Arno, John Hay Whitney, Rudy Vallee, Henry C. Potter, and other extraordinaries of his time -- had he not in a letter to the Yale Daily News, with zeal born of his own and the Jazz Age, attacked the Yale Divinity School lock, stock, and barrel for its lunacy in supporting prohibition. Professor Henry Hallam Tweety of the Divinity School was not amused, nor was President Angell of Yale. Two weeks later, moreover, Beebe locked himself in one of the stage boxes of the Hyperion Music Hall Theater, and, at an appropriate moment in the performance, rose tall (6' 4"), white-bearded, and clerically dressed, and shouted "I am Professor Tweedy of the Yale Divinity School!" and hurled an empty bottle on the stage. President Angell, with an administrative assist from Dean Jones, sent Beebe, in the middle of his sophomore year, north to Boston and Cambridge.

Following a year on the Boston Telegram whose purple works and 72-point orgies are set forth in this collection, Beebe entered Harvard to graduate as a Bachelor of Arts in 1927, but not without having been first suspended by President Lowell for having clobbered a classmate and given him a near concussion. The reason for the attack was literary: Beebe had, through access to some hundred-odd manuscript lines of Edwin Arlington Robinson's verse, conceived the idea of publishing them privately in a rare edition limited to seventeen copies. Without the poet's permission. He did so, distributed copies from Amherst Library to the British Museum, and all would have been reasonably well had not an undergraduate by the name of Wetherby informed Mr. Robinson of it. The poet was pained, but forgave Beebe since the project had been purely bibliophilic with no commercial overtones. Wetherby, however, was hospitalized, and Beebe suspended pro tem.

After graduation from Harvard and following a stint on the Boston Transcript as contributor to its literary section, Beebe's New England days ended. He was ready for the champagne and damask fields of New York.

In June 1929, at the age of twenty-seven, Beebe became a member of the Herald Tribune staff and remained with the paper for twenty-one years. Stanley Walker, mesmerized by Beebe's six-foot-four and sartorial elegance, hired him at thirty-five dollars a week. Beebe started as a reporter frustrated by garden-club doings, annual conventions, minor fires, and occasional assignments as ship's-news reporter. Appearing once in top hat and morning coat among flames and snaking hoses, he was quickly moved to the drama department of the paper. This was again temporary, a mere way station on the road to the ultimate depot: Beebe came into his own on September 9, 1933, with the first tryout in the Philadelphia Inquirer of his column to be called "This New York." The column was further tested in outlying papers as far west as Wyoming, proved successful, and given the final cachet with its appearance in June 1934 in the Herald Tribune itself.

The weekly syndicated (Cleveland, Kansas City, St. Louis, and points west) column dealt only with the good things of this life enjoyed by a limited five hundred members of Café Society. Beebe was not only a fascinated observer and reporter of this Café Society but was himself an active member of it. His wardrobe, spectacular at Yale and Harvard, where he not infrequently brightened morning classes wearing the top hat, tails, and gold-headed walking stick of the evening before, now blossomed to meet the greater demands of the metropolis and his position. He is reported to have owned forty suits, not an excessive number for an individual of means, but certainly a fantastic wardrobe for a working newspaperman during the Depression era. One of his overcoats was minklined with an astrakhan collar, another mink-lined with sable collar. His top hats ranged from sporting dove gray to formal black, and his gloves from fawn-colored doeskin to evening white. It is doubtful that he ever went abroad without a stick.

The New York which he graced included Bleeck's Artists and Writer's Saloon, an extension of the editorial offices of the Herald Tribune; the Biltmore Turkish Baths where he presumably dripped Bollinger; the restaurants and night spots: Le Pavillion, the Colony, El Morocco, "21"; the hotels: the Plaza, the St. Regis, the Madison, and, of course, theater first nights, cocktail scuffles, gourmet dinners, and assorted sarabands in the tight inner circle of socially acceptable Manhattan. Leaving the pleasant confines of this inner island, nothing existed westward until Beebe reached the Pump Room in Chicago via The Twentieth Century Limited. Comparable vast spaces separated him from the civilization of Antoine's and Commander's Palace in New Orleans to the south, and Locke-Ober's in Boston to the north. New Jersey was an unmentionable wilderness, but Pennsylvania securely saved by a railroad, Bookbinder's, and the Stotesburys, Cadwalladers, Mellons, and such.

He was referred to generally as "Mr. New York," an honorific which delighted him and which went down well beyond the Hudson. Walter Winchell irritatingly enough called him "Luscious Lucius," and he was also enviously described as "the orchidaceous of café society." Kyle Crichton termed him "a sort of sandwich man for the rich," and Walter Pritchard Eaton, reviewing Beebe's book The Boston Legend reported: "He betrays an incomprehension in a historian."

In 1937, eight years after his assault on the Big City, Beebe was the subject of an entertaining two-part profile in The New Yorker by Wolcott Gibbs, and, in 1939, made the cover of Life: "Lucius Beebe Sets a Style." Gibbs did other pieces on Beebe's Tribune style and material. The closing lines of the The New Yorker profile deserve a place between these hard covers: "Whatever admirers or detractors say, however, one tribute must be paid. . . . The words of it, with one tiny exception, are from a song made popular in his own time by Miss Ethel Merman, and they can be sung when he is gone: 'Beebe had Class, with a capital K.'"

He was an indefatigable worker, and his production from the time of his arrival in New York to his death in 1966 was constant in quantity and high in quality. He was a "pro." There were fifty-two weekly double columns for the Herald Tribune; a book a year for a total of at least forty books; the once-a-month "Along the Boulevards" feature for Gourmet Magazine; six to ten full articles a year for Holiday, Town & Country, The American Mercury, Cosmopolitan, American Heritage, The Ford Times, Gourmet, Status, Playboy, Esquire, Collier, Railroad, Trains, and other periodicals; and added related matter including book reviews, irate "letters to the editor," a script stint for Hollywood on a film dealing with Café Society, consultant to Hollywood on the railroad film Union Pacific, and personal appearances before clubs and such until he cut these off as a waste of his time. In addition, of course, were the activities providing the material about which he wrote: ranging from white-tie first nights and champagne suppers in New York, Central City, and San Francisco to the patient waiting, with focused camera, for the engine of a great or little train (he loved them both) to come thundering or puffing around a bend in Colorado, Missouri, New York, or Texas.

Lucius Beebe, in the year 1950, opted for Nevada. The decision can be traced back to the Warner Brothers junket which he joined from New York to Nevada for the premier of the film Virginia City in 1939. The town at that time fascinated him on all counts: the citizens were completely normal and uninhibited characters who drank, if they felt like it, firm slugs of scotch or bourbon at the bars with their bacon and eggs, or skipped the eggs and bacon altogether: the residents were descendants of miners and mine operators who had built the town, and, if they ever noticed them, gave not a damn for the opinions of anyone; there were no confiscatory income taxes of any sort whatsoever: this made supreme sense; lastly and above all, there was a newspaper on which Mark Twain had worked, The Territorial Enterprise, one of the most famous papers in this history of the land, up for sale: Beebe and his associate, Charles Clegg, bought it together.

With Clegg, he published for eight years an exciting newspaper, one which took no guff from any quarter and which, as the occasion warranted, fired grapeshot or slammed broadsides at any and all.

In 1960 the paper was sold and Beebe and Clegg took to living during inclement Nevada months in ineffable Hillsborough on the Peninsula south of San Francisco. Beebe contributed from 1960 to his death in 1966 a weekly column to the San Francisco Chronicle titled "This Wild West," balancing his earlier "This New York." The opinions expressed in it were at poles removed from the Chronicle's editorial policy and horrified the owners, who, however, allowed their San Francisco urbanity to triumph over liberal prejudices. A variety of pieces, selected and trimmed down from the full columns, were published in book form in 1966 by the Chronicle under the title The Provocative Pen of Lucius Beebe, Esq.

While maintaining their residence in Nevada, Beebe and Clegg continued their annual visits to New York with occasional trips via Cunard to London. They also traveled the United States in their jointly owned, fabulous private railroad car, Virginia City, an eye-popping legend in its own right, complete with Venetian décor, fireplace, wine cellar, and Turkish bath. Beebe continued producing books and articles to the last: his entertaining The Big Spenders appeared after his death, and for more than a full year magazines printed articles of his which had been submitted before he passed on.

Beebe lived a full and expansive life to the end. He died suddenly, of a heart attack, on February 4, 1966.

-Duncan Emrich

Washington, D.C.

How It All Began

What was the Comstock Lode and how did it come into being?

The Comstock was the greatest bonanza in precious metals ever to be uncovered in modern times and probably in all history, although the wealth of Peru in the days of the Incas may have rivaled or surpassed it. The total wealth in gold of the Incas has never been definitively calculated, but the riches that poured out of the Comstock came close to the three quarters of a billion dollar mark. Two of its mines alone produced $190,000,000 in silver and gold in a space of a few years.

The Comstock, which was first known as the region of Washoe, embraces three communities, Silver City, Gold Hill and Virginia City, the last of which is located directly above its richest mines and is immeasurably the most famous. Virginia City, Queen of the Comstock, is built on the precipitous slope of Mount Davidson or Sun Mountain as it came later to be known, approximately eighteen miles south of the present city of Reno and in a mountain range which forms the eastern barrier of a pleasant series of Nevada lakes, valleys and meadows known as Washoe, Pleasant Valley and Eagle Valley.

For nearly half a century Virginia City and the Comstock Lode dominated the imagination of the world. They produced a generation of multimillionaires whose names are history and the saga of its fabulous bonanzas is an integral part of the mighty body of legend known as Western Americana.

Envision if you will the terrible and wonderful hills of Nevada, winter-bound and gale-swept six months of the year; reposing in the glare of a pitiless sun the rest, but holding locked in their bosom a secret treasure which was soon to raise empires and set the world’s older treasures tottering into the dust, was to finance the American Civil War and bring into being the city of San Francisco as the golden Carthage of the Western World.

Along the eastern slopes of Sun Mountain the fateful year of 1859 there might have been discovered a group of prospectors of far from prepossessing appearance or reassuring mode of existence. They lived in a tent town insecurely located on the east slopes of Sun Mountain and they were induced to a backbreaking existence in this remote and desolate midst by rumors, repeatedly circulated and sometimes doubtfully substantiated by sample ores, of a great bonanza in silver uncovered thereabout some years before by two brothers, Ethan and Hosea Grosch. But the secret had been lost with the death of both brothers and only a ragtag of prospectors, inspired more by shiftlessness to remain in Washoe, as the region was known, than by diligence, continued to putter about Sun Mountain in search of samples rich enough to secure them a homeric drunk every Saturday night and a correspondingly stupendous hangover every Sunday morning.

Peter O’Riley and Pat McLaughlin are generally credited with having uncovered the first significant silver ores in the Washoe. Actually they were prospecting for gold, and the heavy blue clays in which they discovered its traces were but a source of annoyance in the recovery of the precious metal. But one day in the autumn of ’59 a specimen of the “blue stuff” found its way back to a sophisticated assayer in Grass Valley in the California Mother Lode and within a few hours the Western world was hysterical with the intelligence that the despised “blue stuff” was silver in unfamiliar geological form but of almost incredible richness.

The rush eastwards across the High Sierra was on and on a scale of concentration and hurrah which dwarfed to insignificance every aspect of the earlier California gold rush. Within a few weeks almost as many fortune hunters were hitting the trail for Washoe as had voyaged to California overland, via Cape Horn and the Isthmus of Panama in the first swaggering years of Mother Lode gold.

First to cut himself in on the Washoe bonanza was a sanctimonious gaffer named Henry Comstock. As soon as O’Riley and McLaughlin had staked their claims approximately where Virginia City’s C Street now runs, this prophetic fraud arrived smelling powerfully of Valley Tan, a potable essence of hellebore favored by the Mormon pioneers, and announced that Honest Pete and Stalwart Pat had jumped a claim to which he had previous and undisputed title. Comstock had the grand manner and for the occasion the grand manner was inspired to unprecedented heights by frequent reference to the bottle of Valley Tan in his coat skirt. Pat and Pete were impressed and dismayed. Working the claim of another man was a lapse in manners and etiquette in a community where these qualities were distinctly at a premium. Men had, in fact, been hanged for it. Pat and Pete were, therefore, overwhelmed when Comstock grandly allowed that he would permit them to work his claim on a percentage basis, and everyone headed for the nearest tent saloon to celebrate the partnership. Thus by virtual fraud and by fraudulent virtue of Valley Tan did the hitherto despised Washoe Diggings become the world-shaking Comstock Lode.

Next to take his cue from destiny and make an entrance on the now howling Sun Mountain scene was another boozy ancient named James Finney. Like Comstock, he was possessed of a sort of seedy grandeur and he was the lineal grandfather of all the whiskey advertising colonels who today sip their juleps in the coated paper periodicals amidst properties of the Old South. Finney was from Virginia and nobody within hearing was allowed to forget it, suh. He was widely and only slightly favorably known as “Old Virginny.” One epic Saturday night when the camp was still young, while returning to his foxhole in the side of Sun Mountain, Finney found himself taken in wine. Solicitous against the inevitable morning after, he purchased a bottle of Old Reprehensible and headed for home. But on the way catastrophe overtook the Old Dominion. There was a fearful crash in the night and then those within earshot heard the voice of Old Virginny raised in oratorical key. “I christen this God damned (and otherwise qualified) camp Virginia,” screamed Finney into the darkness. He had dropped his precious bottle but he was going to have a christening party out of it if nothing more.

Virginia City had come into being on the Comstock Lode.

Twenty years later the mines of the Comstock had financed the Civil War; they had produced a crop of millionaires unparalleled in the previous history of the world and were on their way toward the billion dollar mark in silver production; they had caused Bismarck to order Germany off silver as a monetary basis and had reduced this once proud currency to the estate of a base metal throughout the world; they had established San Francisco as the most glittering and opulent city of the modern age, built railroads, the Atlantic cable and places in New York, London and Paris, and had elevated sourdoughs to the estate of bank presidents, ambassadors, newspaper publishers and tycoons and had married their children into the titles and aristocracies of the Old World. And Virginia City itself, a metropolis of 30,000 people, had become an integral portion of the American legend, a source of wealth and riches beside which the resources of the fabled mines of Solomon pale by comparison.

These were some of the forces set in motion by Peter O’Riley and Pat McLaughlin whose source and origin will be forever the names of Henry Comstock, the humbug, and Old Virginny, the alcoholic orator.

Fantastically few of the original discoverers of the new El Dorado ever lived to profit from the incredible bonanza they had unearthed. Comstock himself, co-discoverer of everything in sight, accepted $11,000 for the fabulous Ophir Mine and a few years later, an untidy and garrulous gaffer, he made a noisy end of himself with a heavy bore revolver. While their claims, which they sold for $40,000, were producing a total wealth of $17,500,000 for their new owners, Pat McLaughlin was a $40 a month cook on a Montana sheep ranch and O’Riley was dying in a madhouse, to be buried in a pauper’s grave. Alvah Gould, co-discoverer of the great Gould and Curry mine, sold his share for $450 and spent it on the course of a single magnificent carouse in Gold Hill while telling all comers how he had trimmed some suckers. Old Virginny, who had named the queen city of the mighty Comstock, sold out for a quart of whiskey and a stone-blind mustang and he too was in a pauper’s grave while a new generation of Comstock multimillionaires were swaggering through the bourses and money markets of the world. Alone of the first discoverers, Sandy Bowers, of whom there will be a more detailed report later in this volume, lived a few brief years with “money to throw at the birds” and a splendid mansion that is still one of the landmarks of Washoe Meadows down in the valley.

To the pioneers of the Goddess of Fortune was as blind as the Goddess of Justice is supposed to be.

Before I could even choke out my excuse, they all poured out from behind desks and drawing tables, and engulfed me in bear hugs and slaps on the back and shoulders, with all manner of totally out-of-character behavior. This is one weird day, I thought.

But on the heels of the tidings which were borne swiftly across the Sierra there came other men to the Comstock, men shrewder, more resolute and more sagacious. They bought out the pioneers for the proverbial song and remained to become the operators and beneficiaries of the seemingly inexhaustible wealth that had reposed unsuspected through the centuries in the depths of Sun Mountain. Their very names became legendary and Flood, Fair, Mackay, Sutro, O’Brien, Hearst, Mills, Sharon and Ralston will forever be a part of the sagacious saga of the American West.

Other Stories

Money to Throw at the Birds

Perhaps because his mansion is still tangible and visible in Washoe Meadows as a monument to departed greatness, perhaps because he was the first of the Comstock’s millionaires, and perhaps merely because he acted according to his natural inclinations and had a good time with his money while he and it lasted, Sandy Bowers is to this day one of the best remembered figures of bonanza times, the archetype of all the desert prospectors who struck it rich and cut a caper on the strength of it.

Eilley Orrum, the future Mrs. Sandy Bowers, the future Washoe Seeress, the future seeker after royal trophies in Europe, came to Nevada from Salt Lake where she had discarded two Mormon husbands, one of them a bishop of the Church of Latter Day Saints. Her Scotch ancestry made her a frugal and hard working woman and, in a region innocent of almost all traces of domesticity, she was one of the first women to hear the call of the Comstock and the very first one to set up a boarding house there. She “did” for the miners, washed their shirts, and spread a table which was celebrated all along the foothills of the Sierra for its biscuits, beans and other substantial oddments dear to the pioneer digestive tract. With such abundant recommendations, she soon boasted the cream of the Comstock as her guests, “Old Pancake” Comstock himself, “Old Virginny” Finney, Pat McLaughlin, Pete O’Riley and Sandy Bowers.

Bowers was the shrewdest of all the original discoverers of the Comstock which, in the light of his later recorded sentiments and expenditures, may not have indicated an Aristotelian sagacity, but had staked out a small footage in the very center of the lode and he stubbornly refused to part with it for the fleeting and trivial rewards which satisfied his associates. Precisely adjacent to Sandy’s ten feet along the façade of what proved to be the United States Mint were ten identical feet owned by his landlady and laundress, the peerless Eilley Orrum. Whether it was that Eilley even then had a touch of the prescience she later claimed and took a quick peek at the future, or whether it was that Sandy wanted to insure his continued association with the only cook of consequence in Nevada Territory, Eilley and Sandy were shortly married and their claims on the Lode consolidated

It wasn’t such a consolidation as that of Gould & Curry or even Hale & Norcross, but it sufficed to make the Bowers the first millionaires of the bonanza and the first of the nabobs to inaugurate the expenditure of blizzards of currency which was later to be the hallmark of the Comstock success story. In almost no time the first of the stamp mills which were being set up down in Gold Hill was crushing Sandy’s ore to the altogether enchanting tune of $100,000 a month, and Sandy and Eilley, whose rewards to date had been few and whose sacrifices many, lost no time in demonstrating that money talked, and with gratifying authority.

It wasn’t such a consolidation as that of Gould & Curry or even Hale & Norcross, but it sufficed to make the Bowers the first millionaires of the bonanza and the first of the nabobs to inaugurate the expenditure of blizzards of currency which was later to be the hallmark of the Comstock success story. In almost no time the first of the stamp mills which were being set up down in Gold Hill was crushing Sandy’s ore to the altogether enchanting tune of $100,000 a month, and Sandy and Eilley, whose rewards to date had been few and whose sacrifices many, lost no time in demonstrating that money talked, and with gratifying authority.

Innocent of the snobbishness and delusions of grandeur which prompted other Comstockers to seek homes on Nob Hill, in Fifth Avenue or the Rue Tilsit, Sandy and Eilley built a home as near the Comstock itself as was convenient, which happened to be down the hill in the pleasant valley called Washoe Meadows. When it was finished it was an amazement, even for its time, of gilt and plush, cloisonné, ormulo, pouffs, draperies and other bibelots dear to the Victorian heart. Their friends came down from Virginia City in droves and exclaimed out loud that surely no castle nor palace, royal lodge nor viceregal pavilion in all the world could hold a New Bedfor spermaceti candle to it!

The sentiment was not lost on Eilley. If this were indeed a palace then, as its occupant, she must be a queen and Eilley knew all about queens from the Old Country. They called on each other in the late afternoon and had a neighborly cup of tea while exchanging decorous but animated gossip about other queens and knowledgeable royalties.

From that day forward nothing could shake Eilley from the satisfying belief that she and Victoria and the Empress Eugenie were indeed cousins, not even the expressed disbelief of the Lord Chamberlain at the Court of St. James or the indifference to her appeal to Charles Francis Adams, the American ambassador, whom history must forever record a churl for not, somehow, having gotten her at least to a garden party at Windsor.

Sandy was easily persuaded and a grand tour of the courts of Europe was shortly announced in the columns of the Territorial Enterprise and other interested newspapers. Their departure was celebrated by a monster dinner at the International Hotel in C Street and Sandy’s speech upon this wonderful occasion must remain through the centuries a model for frankness and good humor.

Eilly and he, Sandy announced from the fragile eminence of a French gilt chair, had known some interesting people in their time in and around Washoe, Horace Greeley and Governor Nye and old Chief Winnemucca. But now they aimed to see some even more interesting people like the Queen of England on her throne and this was by way of a farewell to their old friends in the diggings. Drink hearty, everyone, because he and Eilley had money to throw at the birds and wanted everyone to have a good time.

Tradition has it that all Virginia City had itself one hell of a time and that the International Hotel still showed traces of their appreciation a week later when Sandy and Eilley actually took off for San Francisco and the steamer to England.

The chilly Charles Francis Adams might prove impervious to the qualities and assets of the Bowers, but as much could not be said for the shopkeepers of Bond Street and the Rue de la Paix, nor even for the Muse of History. Denied access to the presence of Victoria the Good by reason of Eilley’s unfortunate multiplicity of husbands, they were welcomed as only Yankee royalty could be welcomed to the ateliers of dressmakers, jewelers, furniture dealers and collectors of articles of what the age knew as virtu. The record shows them to have been the prize shoppers of the season of 1863-64 and during their stay in Paris alone their drafts against Wells Fargo back home came to more than a quarter of a million dollars. The Bowers had money to throw at the birds and the birds all wore frock coats and the reassuring manner of very upper class tradesmen.

Eilley and Sandy stayed in Europe and England for several years and their claims continued to produce fantastic sums of money to support their wildest whim and most expensive fancy. They called on Eilley’s family in Scotland who plainly didn’t believe a word either of them said and secretly harbored a suspicion that their Eilley had gone in for piracy on the high seas or, possibly, counterfeiting. Somehow – perhaps they were imposed upon, perhaps some generous person highly placed took pity on Eilley’s pathetic hunger for royal properties – they obtained cuttings from the royal ivy which overgrows the walls of Windsor Castle and, armed with this symbol of success, the Bowers returned in triumph to the Comstock.

Several hundred thousand dollars worth of French mirrors, Italian statuary, bronzes, oil paintings, crystal chandeliers, Turkey carpets, morocco-bound volumes of the classics – although Sandy never could tell whether the text was upside down or not – marble fountains and suites of bedroom furniture came with them. But long after she had tired of these rich treasures, Eilley delighted to show visitors and especially friends who had known her in the lean years the cuttings from the Windsor Castle ivy now growing luxuriously over the massive walls of her Washoe mansion. A personal gift from Victoria to Eilley, a royal token of friendship from one reigning monarch to another Very Exalted Personage.

In time, in the late sixties, Sandy died and was buried in the hillside back of his splendid home in Washoe Meadows. The Bowers’ claims ran out and Eilley was reduced to taking in picnickers at the mansion for a living and a little crystal gazing on the side. Then after years of poverty, she joined Sandy in the shadow of the guardian Sierra and under the pine trees that whisper ceaselessly of the golden and irretrievable past. But the ivy from Windsor Castle, which Eilley had tried to destroy when they took her mansion away from her and sent her to the old ladies’ home, grows strongly still, probably the only thing in Nevada which cherishes memories of two queens.

Railroad to Golconda

Beyond any doubt the one Comstock institution that functioned longer, achieved more enduring fame and whose name became more synonymous with Nevada than any other tangible asset except the Lode itself was the Virginia & Truckee Railroad. For more than eighty years of unbroken and useful service its operations were at first the wonder of the railroad world and later the most picturesque of working antiquities. Long after the mineshafts of Hale & Norcross and Consolidated Virginia that brought it into being were sealed forever and long after its builders, the might Darius Mills and shrewd William Sharon of the Bank of California, had routed their private cars for the last time over its circuitous rails, the V & T was a functioning Nevada tradition, a venerable gaffer among the railroads of the world. It had outlived its spendthrift youth and even its substantial maturity, but it still precariously rolled the mail, freight and a few passengers over its grass-grown right of way to become an imperishable actor in the great cavalcade of American railfaring.

Other railroads have had other terminals, but the V & T’s generations of dispatchers now long dead gave it a green light and a clear track without slow orders and straight to immortality.

By the late sixties fortunes of the Comstock were, after a full decade of thundering production, operating in borrasca and the end of their yield was in sight. Because of the freight charges of the teamsters who hauled the ore down to the mills which lined the Carson River from Dayton to Empire only the richest ores were worth processing, and timber with which to shore up the deep stopes, drifts and winzes of the mines was equally prohibitively priced. Millions of dollars in inferior ore lay on the mine dumps below Virginia City and ore worth millions more was almost at hand below ground but was unavailable because of the excessive cost of getting at it.

The Bank of California’s manager on the Comstock was a dapper and infinitely foresighteed little man named William Sharon. Sharon knew that a railroad was what the doctor prescribed for the ailing Comstock. It would take the ore down to the mills at a fraction of the teamster’s prices, thus making the inferior ores now above ground available to reduction, and it could bring up timber from the forests of the Sierra at fantastic savings to continue operation of the mines. But Sharon wasn’t satisfied simply with the idea of building a railroad and taking a profit from its operations in freight and passengers. It might not be said that Sharon was greedy, but he had a remarkably acquisitive intelligence and so, with a grand over-all design in the back of his steel trap mind, he began allowing the mill owners of the Comstock to overextend themselves financially at his bank, took their paper when he knew it to be quite unsecured by any possibility of future earnings and kept the matter of the railroad under his well groomed silk top hat. When the mill owners were unable to meet the obligations and so were completely in the power of the Bank of California, Sharon coolly organized them in a single association, each member of which was obligated to patronize the railroad after it was built and otherwise to do the bidding of the bank in every detail of its conduct.

Then and only then did Sharon build his railroad.

The V & T was originally planned to run only from the mineshafts on Sun Mountain down to the long array of stamping mills along Carson Water, but with the transcontinental railroad now passing through Reno only thirty odd miles away it was inevitably that the V & T should build from Carson to a Reno connection.

The first shovelful of earth was turned for the V & T’s grade in the shadow of the mint at Carson City early on the morning of September 27, 1869, and from that moment down to the immediate present the V & T has participated almost daily, and often in matters of tumult and importance, in the news of Nevada. When, in 1875, the great stone shops and engine houses in the meadows outside Carson City were completed, a local notable named Colonel Curry conceived the idea of a monster railroad ball. For weeks all Nevada was in a tizzy of excitement and newspapers carried daily accounts of reports of the decorations committee, the decisions in the matter of refreshments and how the resourceful colonel was sending to far-off San Francisco for an orchestra at the unheard-of outlay of $500! When the ball itself took place special trains brought the elite of the Comstock down to Carson in their Paisley shawls and broadcloth tailcoats on special trains for the gala event and the last special didn’t head up the grade with its cargo of wilted revelers next morning until nine o’clock. Nevada has never forgotten the great railroad ball of 1875.

Once in operation, the V & T surpassed the wildest dreams of its projectors. Not only did they own the railroad, but the nabobs of the Comstock were carrying aboard it their own ores to mills which they controlled and returning with lumber from forests they also had acquired. Only the cynical would call it a monopoly, but for many years Mills, Sharon and William Ralston, each a third owner of the V & T, divided $100,000 a month in profits from their railroad alone.

Unlike most men of property of a later generation, the owners of the V & T were proud of the appearance of their bonanza railroad and nothing was too good for it. The most powerful engines, the finest and most beautiful rolling stock in all the West made their first appearance on the V & T. Its locomotives were miracles of red paint and gold trim and its coaches were the products of the master car builders of San Francisco and the East. The V & T’s owners had the idea, now quaint and outmoded in American finance, that a fine property deserved well at the hands of its proprietors and that they were under obligation, while pocketing gratifying sums from the V & T, to give the public something in return.

It was inevitably, with the wealth that was pouring from the mineshafts of Virginia City and Gold Hall promising to total a billion dollars, that notables from all over the world should want to see the source of these iridescent wonders. Metallurgists came from Germany, mine experts voyaged from distant Cornwall, the Baron Rothschild and his entourage (a whole special train for them) arrived from London and mere American millionaires, capitalists, stock promoters, newspaper reporters and magazine writers were a dime a dozen in C Street and the bar of the International Hotel.

They all came up over the V & T, in beautiful canary colored coached, in overnight sleepers from San Francisco and Sacramento and in the clever Mr. Pullman’s Palace Cars, each according to his station and means. President Grant, General Sherman, Helena Modjeska, Salvini, Booth, McCullough and David Belasco. Some of the maharajahs of super-finance came in private cars of fearful and wonderful design with vast resources of marble bathtubs, tufted satin boudoirs and brass bound observation platforms. It is hard, even to the enlightened fancy of a later generation, to imagine the V & T yards down the hill a pace from C Street alive of a morning with switch engines shifting traffic and the arriving of hundreds of adventurers, business men and sightseers. But so it once was, and in the evening the light from the crystal chandeliers of stately private cars shone through the drawn silk shades, and women in evening gowns from Paris and New York tripped daintily up their carpeted steps for intimate suppers of quail and champagne. The years of the ortolans on the V & T were very, very splendid indeed.

When the long twilight of its career set in as the mines slowly and finally ceased altogether, the V & T shortly after the turn of the century, changed character from a bonanza railroad to one of rustic and agricultural destinies. It built the Minden branch tapping the rich dairy and ranching resources to the south of Carson City, and for a time the traffic in milk, butter, cheese and stock shored up its declining revenue. But the automobile and the speed highway which paralleled every mile of the railroad’s main line abolished its passenger traffic except for occasional excursions and a few sentimental voyagers into the past and during the last few years the V & T depended almost entirely on the mail contract and a modest source of revenue from heavy freight shipped in on slow schedules.

For a time the railroad was the personal property of Ogden L. Mills, grandson of its original builder, who, a generous, sensible man, kept it running out of his private pocket. No matter how lean the years upon which it had fallen, the V & T could glory in the circumstance, noted on its eightieth birthday, that it was the most celebrated short line railroad in the world.

"Just how colorful the legend of the V & T has come to be," said the Nevada Appeal in the fall of 1949, "is best illustrated by the fact that it figures in more literature than most main line railroads and that no other little railroad ever attracted a quarter the attention of the V & T in books and periodicals, monographs and histories both technical and popular, Bancroft, Eliot Lord, George Lyman, Dan DeQuille and Oscar Lewis are only a few of the writers who have been fascinated by one aspect or another of what Lucius Beebe and Charles Clegg in their Mixed Train Daily have called ‘the Yankee Princess of bonanza railroads.’ It is a certainty that the V & T will enjoy a fragrant immortality as the most literary of all the little feeder lines that once abated time and distance in the imperishable American West."

The original main line of the V & T between Carson and Virginia City was torn up in 1938, but sometimes on clear winter nights when the snow lies heavy on the slopes of Sun Mountain and the coyotes and prairie dogs hold carnival down Six Mile Canyon, old inhabitants of the Comstock hear a soft huff-puffing of wood burning engines and the clatter of couplings and they know, no matter what anyone else may say, that the Night Express for San Francisco is being made up in the yards and that the V & T is still carrying the old bearded Kings of the Comstock and their treasure down the grade to immortality.

Nabobs in Broadcloth

The Comstock was to produce a multitude of great names, some of them of world consequence, others that blazed brightly on a national scale. There was Adolph Sutro, the tunnel builder who was to become one of the most celebrated of San Francisco’s mayors and whose name adorns many municipal institutions surviving to this day. There was George Hearst who was to become a California senator in Washington and whose fortune was one day to finance the most important chain of newspapers and magazines ever to be published in the United States. There was Mark Twain who served his literary apprenticeship on the staff of the Territorial Enterprise and David Belasco who, as a youth, was stage manager at Piper’s Opera. And there was Henry B. Yerington, one of the greatest of Western railroad operators, and Wells Drury, a journalist in the spacious tradition of the nineteenth century newspaper world.

But the names that most fascinated their own generation were those of the Silver Kings, the Lords of Creation, the Big Four of the Comstock Lode, Flood, Fair, Mackay and O’Brien and the other princely seekers and finders of fortune who came to Virginia City with an Ames shovel over their shoulders and departed for palaces on Nob Bill or in the Rue Tilsit.

One of the most arrestingly picturesque of them was William M. Steward, graduate of Yale Law School a graduate too, of the Mother Lode camps of the early fifties and later a Nevada senator and greatest expert on mining litigation in the West. Steward, who was accustomed to try cases involving dangerous characters fully armed with a brace of Navy Colts under the skirts of his frock coat, was the first real law on the Comstock. His interpretation of justice was invariable in favor of whoever might have retained him, but his courage and tenacity were monumental in a generation when both of these qualities were in great requisition. Stewart went on to bigger things in Washington and lived a long and wealthy life in the later Nevada bonanzas, but until his dying day he was a bad man to cross, and the world, or most of it, knew that under his patriarchal beard there was apt to be a shoulder holster and that Stewart’s law was not to be held lightly.

Another of the nabobs of note was John Percival Jones, hero of the great Crown Point fire at the time he was superintendent. Jones also became a Nevada senator and was the driving force behind the now almost forgotten Panamint excitement across the California line in the Death Valley region. Historians remember Panamint as one of the most alluring, deceptive and geographically improbable bonanzas high in the Panamint Mountains where, at Jones’ command, an entire civilization once flourished briefly, sold a blizzard of worthless securities and finally disappeared forever when a cloudburst destroyed the diggings at Panamint city almost without a trace.

Graduates of the Virginia City school of experience enlivened the known world for two full generations.

But hard head and broad shoulder above all the silk hatted rout of Comstock millionaires, king of the bonanza kings and a favorite of fortune whose name was destined to rank with those of Morgans, Rockefellers, Vanderbilts, Mellons and Whitneys, John Mackay was one of the very few, who, when greatness claimed him, never forgot its origins and never altogether deserted the Comstock.

Mackay was one of those who toiled up Six Mile with an Ames shovel on his shoulder. Among the first arrivals from the abandoned riffles and Long Toms of the California Sierra, he went to work in the first shallow diggings on the slopes of Sun Mountain and within two decades was to be known throughout the civilized world as the quintessential American success story. It was his good fortune and that of his associates, more often than not backed by resources of intelligence and determination not always credited in the record, that made the Comstock what Oscar Lewis has called “the nation’s most satisfactory wishing well.”

Like Adolph Sutro, Mackay found the early operations on the Comstock so wasteful and unsophisticated as to be positively repellent, but he was to live to see the management in his own mines regarded by experts as the pinnacle of deep mining technique and the most economical of his generation.

After holding down a variety of jobs in the mines which by this time were appearing along the Lode in florid abundance and observing shrewdly into the conduct, or more often misconduct of their fortunes, Mackay went to work in the Kentuck Mine, taking his pay not in cash to be converted into Saturday night whiskey and Sunday remorse, but in shares in the company. In 1863 the owners of the Kentuck sought to incorporate but found they were powerless to do so without possession of a number of “feet” (all shares were calculated not in dollars but in running footage of the property) owned by one of the original discoverers. The shareholder was reported to be among the Confederate armies fighting in the campaigns of western Tennessee and a fat bonus was posted for the recovery of his proxy.

That was enough for Mackay. The Comstock knew him not for four long months although he reported to have been a passenger on one of Ben Holladay’s overland stages heading for the Mississippi. When he reappeared it was with the missing block of feet and a bill of sale to show his ownership. Mackay never revealed how he secured them but the legend insists he dogged his man into the front lines before Chattanooga and wrangled over the price while Parrott rifles boomed and Minié balls ripped overhead. Now Kentuck could be incorporated and Mackay was for the first time an active capitalist on the basis of his share in the property.

Kentuck turned out to be a bonanza of modest proportions – over a period of years it produced about $5,000,000 – but his share was enough to put behind Mackay forever his days as a $4 pick-and-shovel man or later $6 as timber worker. Once in his Mother Lode days Mackay had remarked that when he made $200,000 he was going to retire and that the man who wanted more was a fool, but success was now in his veins and with the profits from Kentuck he joined forces with James G. Fair, an alliance which was eventually to lead to the Big Bonanza and the emergence of the kings of the Comstock.

The story of the Big Bonanza is told in more detail elsewhere in this volume, but its discovery made Mackay and his associates, Fair, Flood and O’Brien, the one-time San Francisco saloon proprietors, into men of incredible consequence. Of the four, Mackay proved the most capable of bearing the almost intolerable burden of fantastic wealth.

Mackay was married in Virginia City in the parlor of Slippery Jim Fair’s cottage to Marie Bryant, widow of a Downie-barber, in 1866. It was the beginning of a saga of social dazzlements and unparalleled displays of wealth which were to astound even blasé Paris and London in a blasé age, and whose echoes were reawakened in the world press of the 1920’s when Mackay’s granddaughter Ellen was married to Irving Berlin over the aristocratic protest of the existing Mackay family. To this day Mrs. Berlin is a frequent pilgrim to the Comstock to revisit the scene of her might grandfather’s mightiest triumphs. Mrs. Mackay, now armed with formidable financial resources and a naïve determination to display them, removed herself permanently from the United States and set out to conquer formal society in the Old World while Mackay himself, glad to be quit of frivolities, footed her bills on condition that he should be omitted from her campaigns and conquests.

Now without a sense of the ridiculous, Mackay made it a point, upon the occasion of his infrequent visits to his wife’s palaces in Paris and London, to affect the uncouth American millionaire as foreigners expected him. He resolutely refused to learn French, thereby forcing his dinner partners to converse in English to their notable disadvantage. Instead of the rare clarets and noble champagnes served by Mrs. Mackay’s wine stewards and major-domos he insisted on a shot of straight Bourbon with the pheasant. He took a mildly malicious pleasure in recalling his boyhood days in Dublin and insisted that his family’s pig shared the parlor in the best shanty Irish tradition. He was, in a word, a trial while among the dignitaries, so that his wife was glad to see him depart as soon as possible for San Francisco or his beloved Comstock. In actuality Mackay was an extremely well read, urbane and polished man of the world in which he lived.

The whole tally of Mackay’s charities will never be known to anyone. Almost in their entirety, and that was in the millions, they were contributed to causes he considered worthy on the condition that they should be absolutely anonymous. Such institutional benevolences as the Church of St. Mary’s in the Mountains in Virginia City and the Mackay School of Mines at Reno could not well be hidden, but there was quite literally loans to oldtime friends on the Comstock and donations to worthy beneficiaries running into the millions. It was because of this patrician disregard for expenditures in what he considered to be commendable channels that at Mackay’s death in 1902 his business manager was able to tell the reporters: “I don’t suppose he knew within twenty millions what he was worth.”

Mackay was the greatest example of the Comstock’s incalculable power for good. The wealth he wrested from the California and Con Virginia mines was translated into continental railroads and trans-Atlantic cables, telegraph systems, sugar refineries, copper mills and productive real estate. Perhaps, indeed, probably he derived pleasure from the power and authority his great fortune gave him, but the Comstock nearly half a century after his death, remembers him for a disillusioned remark he made one night in the Washoe Club at a time when his income was close to a million dollars a year, a sum the equivalent in purchasing power of four or five times as much today.

“I don’t care whether I win or lose,” he told Dan De Quille. “And when you can’t enjoy winning at poker, there’s no fun left in anything.”

Perhaps that will serve as John Mackay’s epitaph until a better one comes along.

Sunset Over the Sierra

For nine decades now the Comstock has been an integral part of the legend of the American West. For nearly half of this period it was a produce of wealth in one of the most tangible of its many forms and for the other half of its inhabited and exploited existence it has been a romantic fragment of the national history of the land. It has inspired a wealth of lore and literature to the extent of a very considerable bibliography of serious books and has served as a background for a good deal of fiction which never surpassed the actual recorded fact. It has occupied space in the American consciousness out of all proportion to its geographic size or population. Even today it advertises itself to the tourist trade as “the livest ghost town in the world” and there is a surprising degree of truth in this brash boast.

The shrinking violet could never with any plausibility be selected as the official flower of the State of Nevada.

Where the bonanza kings left off on the Comstock the literary lions took over. The legend of the Lode is as completely irresistible to writers as ever the original “blue stuff” was to James Finney or Pat McLaughlin, and its various aspects have engaged such first-rate men of letters as Oscar Lewis, Eliot Lord, Samuel Bowles, Sam Davis and Wells Drury. Even the Virginia & Truckee Railroad is the subject of a very respectable bibliography and the learned treatises on the mining of Comstock are beyond accurate counting.

Surprisingly enough, however, the Carson River, or Carson Water as it is known in the stately old phrase, has never come in for its share of romantic treatment although it is one of the most romantic little rivers in the world. Probably the fact that it is not navigable and that no vast civilizations were ever borne upon its tides has led to this neglect, but Carson Water made possible a great and spectacular productivity as ever floated upon the Mystic, the Ohio or the Colorado. Without it the milling of the Comstock ores would have been impossible by any process known to the nineteenth century and the necessity for transporting ore over vast distances to mills in other parts of the land would have been incalculably costly.

The Carson is well worth the attention of a curious and enquiring generation. A remote and lonely stream, it rises in the foothills of the High Sierra, flows briefly north and east to its appointments with destiny and disappears ingloriously into the Sink of Carson without every knowing the sea which is the objective of almost all respectable and conventional rivers. In spring it is a rushing torrent that inundates vast meadows and downloads around Minden and Gardnerville. By midsummer it is a placid meander whose pools and backwater entice the judicious picnicker and occasional crayfisherman in the neighborhood of Empire and Dayton. In winter it is a gelid streamlet impervious alike to the devisings of mankind or the zephyrs of Washoe. Always it is a lonely and often a beautiful little river winding its way to a lonely and geologically improbable end.

But once it was a river of mighty consequence. When its stamping mills and reducing plants stretched for miles above the Carson City and Empire its waters were carefully husbanded and used over and over again by the successive mills along its banks. Its existence was the basic fact that lay behind the construction of the railroad. Its presence made possible all the operations of the far-reaching and consequential Comstock. It was a river of humble origins and appearance but of weighty importance in the affairs of men. The locomotives of the V & T prowled beside the river on a vast network of spurs and sidings, but today little remains save an occasional cement foundation or vast and ruined machinery sprawling like the skeletons of prehistoric monsters in a wilderness of vines and scrub trees.

There are other pleasant places to explore around the Comstock. Few persons other than native Nevadans know that the Geiger Grade on which they approach Virginia City from the main highway at Steamboat Springs is not the original Geiger over which the stages of Wells Fargo toiled with their treasure until the coming of the railroad is still available to traffic a few thousand feet from the surfaced grade and is an infinitely more picturesque and exciting drive.

Then there is Six Mile Canyon which leads by a precipitous and craggy route down to Sutro past the ruins of a score of once tremendous and vibrant reducing plants and stamp mills. As lately as 1904 the great Butters reducing plant was built to employ 300 workers in Six Mile, but all that remains today is a heap of ruined masonry, mute testimonial to unjustified optimism. And there are agreeable and exploratory drives to be made to Jumbo and Como, but they are not strictly speaking a part of the Comstock.

The years of the Second World War were bleak ones for the Comstock. The V & T had misguidedly torn up its tracks between Carson and Virginia and the rationing of gasoline eliminated the tourist trade almost in its entirety. For lack of repairs whole blocks of buildings in the lower town collapsed and disappeared, their structural economy having been sawed up into firewood. Mining was prohibited by the government and without mining or tourists and with a diminishing supply of liquor Virginia City was in a bad case.

Now, however, the Comstock is enjoying the sort of boom it dreamed of during the dark days. Interest in its historic aspects becomes greater with each passing year and the presence of small but distinguished literary colony adds impressively to the town’s prestige. Its literary lights include Roger Butterfield, author of “The American Past”; Duncan Emrich, assistant librarian of Congress for American folklore; Walter can Tilburg Clark, whose “Oxbow Incident” and “Track of the Cat” have been national best sellers; and Irene Bruch, a lady poetess in the best bohemian tradition of the craft. If this were not distinction enough for a community of 400 persons, Doctor Emrich’s wife is author of a number of well known juvenile books and Katharine Hillyer and Katherine Best are magazine writers of national fame. The Reno Chamber of Commerce, which takes a proprietary interest in all the adjacent countryside, never misses an opportunity to point with pride to Nevada’s mining town culture.

A number of the town’s most famous structures were destroyed in the Great Fire of 1875 and most of its architecture today dates from that and succeeding years. Most notable of the post-conflagration landmarks is the Roman Catholic Church of St. Mary’s in the Mountains whose original was among the losses that dark day in October ’75. John Mackay was frantically engaged with his own workmen in saving the lower workings of his Consolidated Virginia Mine when news was brought to him that St. Mary’s was gone. In the gloom and excitement of the moment Mackey promised to “rebuild twenty churches” if his mine was saved and he later handsomely lived up to his promise, although a single edifice seemed sufficient for the religious needs of the community.

Perhaps the most apparent and certainly the most animated indication of the Comstock’s new lease on life and on the bonanzas of tourism is the reactivation of the celebrated newspaper The Territorial Enterprise, which, after thirty-six years of suspension, was revived as one of the authentic properties of the Old West by former New Yorkers Charles Clegg and Lucius Beebe, now residents in Virginia City and described by Stewart Holbrook as “Nevada’s peerless ambassadors to less favored parts of the world.”

The title and good will, such as it was, of what had once been the most famous of all frontier newspapers, was a latent asset through a succession of abandonments and mergers of the feeble and faltering Virginia City News. The new tycoons of newspaper row purchased the News with a circulation of fewer than 200, reverted to the historic name and style of The Territorial Enterprise, and set about relocating Virginia City on the map. Removing from a job printer in Sparks, a suburb of Reno, they erected a handsome modern printing shop in the rear of the still standing Territorial Enterprise Building at 24 South C Street to which the paper had moved in 1863. The Enterprise Building is actually the property of Roy (“Buffalo Bill”) Shetler, who maintains it as a Mark Twain Museum, and the editorial and business offices of today’s newspaper occupy rented space there while printing its editions in an annex invisible from C Street.

The new owners set about recasting The Territorial Enterprise not so much in its original format as in a style a good deal more atmospheric than it had possessed in the days when Joe Goodman and Dennis McCarthy were the primal movers of its destinies. All its headlines, standing and departmental heads, and much of its advertising are hand set in rare and beautiful fonts of Victorian elegance, many of them museum pieces, while its actual contents are the up to the minute or at least up to yesterday’s news of Nevada and the West generally. From a limping 200 and nineteenth place among Nevada weeklies, with no twentieth, The Enterprise in less than three years came to be, by Audit Bureau of Circulation’s rating, the largest weekly newspaper in nine Western states including, naturally, Nevada. With a circulation in excess of ten times the population of Storey County in which it is published, it has climbed from four slim pages of local news to twenty and twenty-four pages of costly national advertising and to the position it occupied of old as the free-wheeling wonderment of the Western World.

Its present editors are scarcely more inhibited than was the redheaded young man named Samuel Langhorne Clemens who, as a member of The Enterprise staff in 1864, started signing his stories with the byline Mark Twain. Possessed of a genius for chaos, they enjoy nothing so much as the controversy of “hey, rube” proportions, and as a result The Enterprise has occupied a great deal of space in the national prints, to the ultimate enrichment of Virginia City itself.

While it may be remarked parenthetically that a ponderable number of Comstockers have no slightest notion of what The Enterprise is all about, they have no least hesitation in pocketing the tourist dollars it attracts to C Street, and subscribers of discernment in Boston, Houston, Baltimore, and Paris enjoy the continuity it establishes with the great days and the riding years of the Old West.

An indication of Virginia City’s awareness of its ever crescent value as one of the last valid repositories of the Old West, both in spirit and in concrete being, is the recently enacted regulation aimed to preserve the façade and architecture of the center of the business community in and around C Street formally known as “Virginia Old Town.” The legislation, similar to that which protects the historic properties of Paris and the Vieux Carré in New Orleans, prohibits alteration of existing buildings or the erection of new structures until the architecture involved has been approved of by a board of qualified experts in the field of Western atmosphere.

The threat of invasion by hamburger stands, motels, drive-ins, and filling stations of moderne aspect provoked the notoriously cantankerous and uncooperative Comstockers to a concert of action altogether unprecedented in the community’s annals in modern times.

Amateurs of the American past and of the old West see in Virginia City one of the few remaining examples of the hell and high waters days of the frontier and the individualist. There are vestigial remnants of the nineteenth century elsewhere in the land, notably Central City and Leadville in Colorado; Tombstone, Arizona; Columbia in the Mother Lode; and the other Virginia City, that one in Montana. None of these however seem to retain the ancient flavor of character at once raffish and sophisticated that abides in the Comstock. The great days may be irrevocably gone but those which have followed them in Nevada are still sufficiently spacious to serves as a reminder of a notable manner of life patterned in the American way.

The Big Bonanza

Bonanza is a Spanish mining word meaning solvent, profitable, in the money, or paying off. Its opposite, borrasca, just as common usage in the jargon of mining but less in popular circulation, means to be operating at a loss.

The phrase, “The Big Bonanza,” usually capitalized to set it apart from all other discoveries of precious metals just as, in many communities “The Big Fire” sets some particularly notable holocausts apart from all others, is conventionally used in the lexicon of the Comstock to describe a single momentous uncovery of riches at a specific date and does not refer to the profitable working of the Comstock Lode as a whole.

The Big Bonanza, which was to produce one hundred and ninety million dollars in almost pure silver in a single block of precious metal, was to raise to almost unbelievable wealth an entire new dynasty of American millionaires and was to create panic, terror and disintegration on all the bourses, stock exchanges and money markets of the world, was the result of good fortune, great resolution, an uncommon knowledge of mining and an ability to keep a screaming secret on the part of four astute and determined men. James Flood, James Fair, John Mackay and William S. O’Brien were no ignorant prospectors who stumbled by mischance upon fantastic wealth. They were extremely capable mine operators who were sure there was a tremendous bonanza awaiting the proper exploitation of their property and who clung to this belief against the better judgment of others until it was justified on a scale that made them the most envied men in the world.

By the year 1873 the mines of the Comstock had been in and out of bonanza half a dozen times. After each slump, new mining methods, enlarged facilities or renewed persistence upon the part of geologists and mine foremen had uncovered new treasure houses deep on the slopes of Sun Mountain. Blow hot, blow cold, Virginia City was always either on top of the world or in the lowest dumps of depression. The mines were played out, so the rumor ran, and the miners and prospectors were off bag and baggage to the newly reported strikes along the Reese River and in the White Pine district. The huge bonanza in Crown Point dispelled the gloom. The ores were getting so lean they weren’t worth milling. The Virginia & Truckee Railroad disproved that fallacy and the goose hung high again.

By 1873 the Comstock had been through a dozen depressions, created scores of millionaires, was the occasion of a thousand suicides, and had alternately panicked and rejoiced the Mining Exchange down in San Francisco until hysteria seemed the normal aspect of life and sudden riches and sudden ruin the conventional order of things.

The partnership of Flood, Fair, Mackay and O’Brien had profited in a fairly substantial way from such mines as Kentuck and Hale & Norcross in which they had interested themselves. They were on the way to becoming men of substance, but that meant nothing in the dreams which haunted men on the Comstock, and besides they had lost heavily in prospecting the unprofitable Savage. Fair and Mackay worked as superintendents on the actual scene of operations in Virginia City while Flood and O’Brien, the former saloon keepers and contact men, represented their interests in San Francisco, watched the market and spread information which advanced or depressed stocks to the advantage of the partnership.

Mackay was obsessed with the belief that there was rich ore to be taken out of two despised and then comparatively worthless properties lying adjacent to each other in the middle of the Comstock profile. Consolidated Virginia and California has produced nothing but assessments for their stockholders although they were strategically situated between the rich and prosperous properties of Ophir and Best and Belcher, but, at Mackay’s word, Flood and Fair down in San Francisco began buying stock in California and Con Virginia at depressed rates on the San Francisco market and, when control of the property was assured, Mackay and Fair sank an exploratory shaft in Con Virginia, obtaining at the same time permission from the management of nearby Gould and Curry to join it with an exploratory drift from that mine’s 1,100 foot level. Fair was below ground the day his workmen cut into an eighth of an inch of pure silver ore. Instantly he ordered the drift turned to follow this elusive seam. It ran briefly and disappeared, repeating the performance for several weeks until one day, well inside the bounds of Con Virginia it amazingly opened into a vein fully seven feet wide. The partners held their breath, both in C Street and down the hill in Montgomery Street. They held their counsel, too, and continued to buy up Con Virginia and California whenever a block of either stock appeared on the market. At the bottom of the shaft of Con Virginia a new drift was cut following the course of the one higher up and after tunneling less than 300 feet Fair and Mackay cut into a block of almost pure silver fifty-four feet wide and of as yet undetermined height and depth.

This was it. This was The Big Bonanza.

The assays, which ran as high as an unbelievable (considering the volume of ore in sight) $630 a ton, were kept secret. Con Virginia began producing immediately but not through its own shaft. That would have given the C Street tipsters a notion of what was toward. It was brought up in dead of night by trusted gangs of specially selected and paid miners through the shafts of the friendly Gould and Curry.

The pulse of the market rose and fell in normal sequence, but no word or action of the partners indicated that wealth to pale the treasure of the Incas was already in their hands and they continued to buy up Con Virginia and California whenever it appeared on the market. They called a meeting of the stockholders and increased the capital stock. They blocked the bonanza and knew they were among the richest men in the history of the world. Then they let their monstrous cat out of its bag.

Calling in Dan De Quille, mining editor of the Territorial Enterprise, Fair assumed great indignation about the treatment he and his partners had received from the San Francisco papers, where they had long been regarded as fly-by-nights and common stock riggers.

“You tell them the truth, Dan,” said Fair with a fine show of outraged virtue. “Go down there in Con Virginia and just tell them what you see.”

De Quille, a trusted and conservative mining reporter with years of Comstock experience behind him, went down in the mine, made his own measurements and computation and was so frightened by the result that he cut his estimate of the ore in sight by one half before publishing the result in his paper. Even thus halved, his story next morning announced there was visible in Con Virginia $116,748,000 worth of “finest chloride ore filled with streaks and bunches of the richest black silver sulphurettes.” The implication, of course, was that California might be even richer since it lay adjacent and presumably shared the same ore mass.

Under the careful management of the four men who henceforth were to be known as the Kings of the Comstock, the valuation of the two mines on the San Francisco Exchange rose from $40,000,000 to $160,000,000. At news of its discovery, Bismarck ordered Germany off the silver standard. It made the dateline of Virginia City more important on news stories throughout the world than those of ancient capitals: London, Rome, Paris, or Madrid. It enriched many; it touched some with scandal, and its implications, fraudulently implemented by promoters, were eventually to cost speculators on the Pacific Coast nearly $400,000,000. These were the gulls who came to believe the entire Comstock was founded on riches as authentic as those of California and Con Virginia. But the four who had brought in the Big Bonanza and actually controlled its real and tangible riches became the lords of creation, peers in the society of Crassus and Croesus, the Great Inca and the Indian Maharajahs, and eventually the Rockefellers and Mellons, the richest men of all time in the known world.

A Dream of Adolph Sutro

Among the earliest comers to the Comstock in the white heat of its first fame in 1859 was Adolph Sutro, a Jewish cigar maker from San Francisco. A contemporary, in Washoe chronology at least, with such future nabobs as George Hearst and John Mackay, Sutro was possessed of an orderly and practical mind to which waste was anathema and the useless and unscientific dissipation of energy an abomination.

Upon arriving in Virginia City Sutro set out on a tour of inspection of the mines then operation. Profit-taking started at the very roots of the sagebrush on the slopes of Sun Mountain, and such easy access to riches had banished all thought of anything even approximating scientific mining from the intelligence of the first miners. Ophir was little better than a cut in the hillside. Gould and Curry was being worked with Mexican peons under contract labor and no attempt was being made to reclaim any but the richest ores. The waste of less valuable ores was stupefying and they lay abandoned in the dumps to the value of hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Sutro’s whole being was outraged. Here, he reflected, was a profile specifically created by nature for the easy, orderly and scientific working of its resources. The ore deposits lay on a hillside whence gravity, only slightly implemented by human ingenuity, would take them with an absolute minimum of waste labor down to the millsites along the Carson River. Obviously instead of sinking shafts straight down to follow the leads and fissures in their underground progress and then timbering up enormous chambers underground, the original shafts should be supplemented by a tunnel or tunnels dug in to meet them at right angles from lower down the hillside. Through this tunnel ore could be carried by gravity rather than by the expense of vast quantities of fuel to hoist it hundreds of feet vertically to the surface. Via the agency of a tunnel, too, it would be anywhere from five to six miles nearer Carson Water when the ore emerged to the light of day and all that distance would have been eliminated by a simple gravity-activated underground tram instead of by costly teaming down the side of the mountain. The thing was so obvious as to be almost laughable.

But Sutro’s tragedy was that to the easily satisfied miners of the Comstock’s early years, his project was laughable. Why in heaven’s name, they asked, should they be put to the trouble of digging a tunnel six miles long, even if such a project were practicable, which of course it wasn’t, to ventilate shafts that were now practically open to the sky and carry out ore that already lay on the surface? The miners, who at this stage were recovering surface values, never foresaw that in a few weeks or months their shafts must sink to levels where their digging and maintenance would prove increasingly costly and hazardous and where their depth would easily justify a lateral tunnel dug in to meet them. Nor did they or even Sutro foresee the floods of boiling water which, at increased depths, could be removed only by the most powerful and costly surface pumps, yet easily could have been drained by the very tunnel Sutro proposed at but a fraction of the expense of tremendous pumping plants working night and day on a year round basis.

Five years after the Comstock’s first excitements, its name was beginning to lose its power. The greedy manner in which the mines had been operating was having is effect and, more than anything else, their output was imperiled by water. Shortly thereafter it was to be entirely suspended. Perhaps the most dramatic example of the manner in which subterranean floods were able to defeat the shrewdest and most resolute superintendent was at Ophir. Ophir was the first to experiment with steam pumps in the hope of abating the seepage which, with every foot its shaft was sunk, became stronger and less controllable. A fifteen horsepower steam-activated pump was erected in San Francisco and installed while the Compstock held its breath. The pump functioned magnificently but it was soon apparent that, despite its satisfactory performance, it would require more and bigger pumps than existed anywhere to make an impression on the underground floods. Half of the mines along the Lode were closed and Virginia was in the midst of its first great panic.

Again Adolph Sutro came forward with his proposal of a tunnel to the Carson. His arguments now seemed more valid than they had before because, besides ventilating the mines and facilitating the economical, easy removal of ore, such a bore would perhaps drain off the waters that were plunging every shaft on Sun Mountain into borrasca. But there was powerful opposition to Sutro among the mine operators who were determined never to pay the two dollars a ten royalty that Sutro proposed to charge to defray the tunnel’s cost of construction and operation. Sutro obtained articles of incorporation from the Nevada Legislature in 1865 but funds were not forthcoming from any source at all. Sutro pleaded with Congress in Washington for funds. In vain. He submitted prospectuses to Commodore Vanderbilt and William B. Astor in New York. In vain. He received encouragement in France but the approach of the Franco-Prussian War put an end to that hope.

It remained for one of the Comstock’s periodic disasters to do more than all his own efforts had availed to promote Sutro’s tunnel. In 1869 there occurred the terrible fire in the Yellow Jacket Mine which cost scores of lives and it became apparent to everyone that, had Sutro’s tunnel been in operation as a subterranean fire escape, the holocaust need never have exacted so frightful a toll in life and treasure. With the united opinion of the Comstock miners behind him, Sutro scraped enough funds to begin work on his tunnel a short distance up the slope from Carson River in the fall of 1869.

Work on the tunnel was slow. Sutro had to meet a score of crises, most of them of financial nature. The mines were booming again and a period of bonanza was earning unheard-of wealth for the operators of the mines while employment, too, was up and Sutro experienced difficult in recruiting workmen for the construction of his project. The construction of the Virginia and Truckee Railroad was also a threat since its completion materially cut the cost of freighting ore down the mills along Carson River, a boon which Sutro had planned to confer on the Comstock himself.